The midnight zinnias.

After my summer class ended this afternoon, with the usual term's-end mingle of regret and relief, I spent a good part of the rest of the day reclined in a pair of chairs on a lawn, my feet bare and sunned, my ears full of more Sufjan Stevens. (Seriously, have I recommended him to you yet? The concept albums, Illinoise (2005) and Greetings from Michigan (2003), are both great, but the album that came between them, Seven Swans (2004), might be my favorite right now, for the spare, devastatingly complex simplicity of its lyrics and its strings. Try "To Be Alone With You," for one, but don't let yourself think it's a romantic narrative.)

And that was good enough, that sitting in the chairs in the shade on the lawn, trying to get comfortable enough to put my thick and swimming head back and to sleep. Or at least it was almost good enough, perhaps a shade short.

And then a poem walked up and wanted to be written down, and so I started. And then I stalled, distracted from the poem by what was not the poem, what could not be the poem, what the poem needed to excise in order to exist.

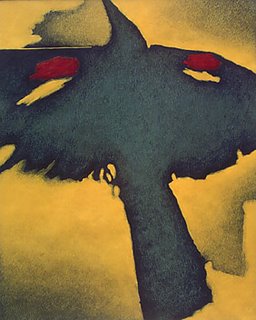

Striding away from the chairs in the shade on the lawn, I reached the man selling vegetables near the path. Beside the multicolored squashes and the tiny tomatoes and the greens leafing wetly in plastic bins, there on the red bench, there were the vats of zinnias, yellow and red and orange and fuschia and white, their stems rich and strong below the gorgeous multifarious fullness of their blooms. "How much are your flowers?" I asked the man selling the vegetables. "Three for a dollar," he said.

I walked the gravel path toward home in the five o'clock sun bearing my nine perfectly chosen zinnias, these sweetest and boldest of favorite flowers a gift to the girl who waited for years to get blooms from another before deciding to give them to herself, over and over and again. Now, in the half-dark of the porch, I look at these stems, and at their profusion of petals, and I memorize all over again the ephemerality of sweetest and boldest things, and my hopes (I had written faith, but I'm still struggling that way) that such profusion cannot go unseen and unneeded--that it fills its presaging purpose, that it leads to some greater, necessary growth, that brightest beauties don't go wasted.