In memoriam.

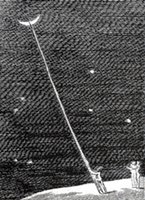

My favorite William Blake image is a small one, the ninth plate from The Gates of Paradise (1793). In it, a hatted man has hitched his ladder to a crescent moon and seems about to ascend; a couple stands behind him, embracing. In The Illuminated Blake, a compendium of Blake's illuminated works, David Erdman's commentary on this image describes the man as looking back at the embracing couple, the woman of whom is "not too busy to wave or direct him upward" (273). As I peer at the image, knowing full well that I don't have any reproductions good enough to allow me to quarrel with what Erdman was undoubtedly able to see while he used the originals and magnification, it always looks more to me as though the climbing man is entirely focused on his impending ascent. Blake's key for this image explains that the man is "On the shadows of the Moon / Climbing thro Nights highest noon" (Erdman 278). These details are mostly beside the point of this writing, which has more to do with this image's caption than anything else (though the image itself encapsulates so much that is important to me about the way I exist in this world). At the bottom of this plate, which is one of the only ones that didn't undergo some kind of serious change when Blake re-released Gates of Paradise perhaps a quarter-century after first engraving it, Blake includes the simplest of cries: "I want! I want!" This spring, I finally found a coffee mug bearing the engraving on one side and the caption on the other. I'm using that mug today.

My favorite William Blake image is a small one, the ninth plate from The Gates of Paradise (1793). In it, a hatted man has hitched his ladder to a crescent moon and seems about to ascend; a couple stands behind him, embracing. In The Illuminated Blake, a compendium of Blake's illuminated works, David Erdman's commentary on this image describes the man as looking back at the embracing couple, the woman of whom is "not too busy to wave or direct him upward" (273). As I peer at the image, knowing full well that I don't have any reproductions good enough to allow me to quarrel with what Erdman was undoubtedly able to see while he used the originals and magnification, it always looks more to me as though the climbing man is entirely focused on his impending ascent. Blake's key for this image explains that the man is "On the shadows of the Moon / Climbing thro Nights highest noon" (Erdman 278). These details are mostly beside the point of this writing, which has more to do with this image's caption than anything else (though the image itself encapsulates so much that is important to me about the way I exist in this world). At the bottom of this plate, which is one of the only ones that didn't undergo some kind of serious change when Blake re-released Gates of Paradise perhaps a quarter-century after first engraving it, Blake includes the simplest of cries: "I want! I want!" This spring, I finally found a coffee mug bearing the engraving on one side and the caption on the other. I'm using that mug today.What I want (I want!), this afternoon, is to mourn the loss of an excellent dog, my favorite Ohio dog, one of my longest-standing Gambier friends. You will recall, perhaps, my writing about the beginning of his decline, back in April. As it turned out, he had only two more months of life beyond that writing. On Thursday evening, while I was out cavorting in my midsummer's sense of lingering, yearning youth, my friend was dying in his home, his breath caught by a thunderstorm, his life stopped by a fear and trembling that became an unconsciousness that (they tell me) stayed until a sigh from the backseat of the car, speeding to the vet, came to stand as his last sign of life.

Yesterday afternoon, coming home from my morning and afternoon teaching sessions, which had more than their usual share of strange hilarity, I saw my excellent friends walking their younger dog. The absence of my dog friend was no surprise; he has not gone on a long walk since April. Nor was one friend's nose-blowing a sign; I assumed he had a cold about which I didn't know because I hadn't seen him since our gala-fabulous dinner (at which I was distractable to the point of not being able to sit still, and of barely being able to finish my dinner) on Saturday night. Because we're in Gambier, I stopped my car in the middle of the road to ask how they were. "Well," came the reply, "we're fine, but Toby died last night." I parked the car in the driveway (for they were right outside my house when I met them) and started getting the story, but what I also started getting was numb, numb beyond reaction or inscription, numb beyond sensitivity and sympathy, numb beyond all the years of love and company I have spent with a dog I will never see again, a dog I didn't see even once in the five days leading up to his death, a dog I would in any other week have petted and communed with at least a handful of times.

I was looking the other way when he went; I was busy helping my young readers try to make sense of why it matters to people in Beloved that they were looking the wrong way when the four horsemen of a latter-day apocalypse rode into town to cap off Sethe's unliveable life. I was busy feeling wet grass under my toes, busy trying to get a match to light a firework, busy scanning anapests under the table during a discussion of a book I didn't like, busy teaching others how to teach, busy, just busy. As he lay dying, I was busy eating carrot cake in the power-outed dark on my porch, busy watching a moth fly at his own candlelit shadow on my porch ceiling again and again, busy trying to figure out how to explain the contradictory vagaries of desire and regret and love and sorrow to eighteen-year-olds, busy trying to figure out how to let myself simply put on a pair of headphones and be sung to sleep by music I don't know well yet, in a full, early, foreign dark.

"There's nothing you could have done," said my young poet friend, who happened to be the first to arrive at the house after I'd gotten the news, and I know that he is right. And I don't think that what I feel today is guilt. I think that what I feel is sorrow, though not for what would seem to be the right thing, not just yet. I'm sorrowing over my absence of surprise, which feels too uncomfortably akin to an absence of caring, even though I know it is not that absence. "I don't know when it's going to hit me," I told my friend yesterday afternoon, "but it sure as hell hasn't yet." Later in the evening, as he and the rest of my teaching staff were sitting about in a pie stupor, in our variety of supine poses all over my front porch's furniture, the dog nosed worriedly into my conversation, pawing the floor with his left front paw just as he always did when he wanted the thing he could not articulate but that he knew we would intuit because we knew him well. I told a Toby story or two--for one, the story about his being taken to Texas to stay with my excellent friend's parents in 1995, left there with the leaving-home refrain "We'll be right back," not to be picked up until a year later when my friends returned from their year of teaching in England--and after a full silence, my friend quietly asked the nine-hour follow-up: "Has it hit you yet?"

"No," is all I could say then, all I can say now. No. No, but also why, why, why don't I feel it yet, where is it, when will it come, when will it hit me, when will it hit me, and then I realize that as I keep asking when it will hit me, the antecedent of "it" is changing, is becoming all those losses and deaths I have missed over the years, all the sorrows I have not felt, whose blanknesses I have not understood, so that when I think O for the loss of a dog, O, O, what I am crying with these tears that won't come is O for the loss of my mourning for the grandparents who loved me in ways I didn't understand until it was nearly too late. O for the loss of my grandmother who went to sleep one night and died not long after, leaving my grandfather unable to find us (we were at the beach for a few days longer; only she had known where we were), leaving my parents to depart for Detroit so swiftly that they forgot their clothes and my mother had to borrow one of her mother's dresses in order to go to her mother's funeral, leaving the preparations to come together so swiftly that my brother and I could not get to Detroit in time to be present at the funeral of a woman so capacious and so loving and so proud that I would give nearly anything just for a morning over toast and butter and honey at the breakfast table in the yellow kitchen, would give nearly anything to have her make me a cup of coffee in the percolator, to trade pie crust secrets with her, even to know what her favorite kind of pie was.

I missed my grandfather's death, as well, both times it happened: I was in England (with my excellent friends, then my teachers, while their dogs were in Texas) when he had the terrible car accident that catalyzed his Alzheimer's (leaving him fulfilling my worst nightmares, the obliteration of consciousness's power, perhaps placing the nightmare in my genetics). I had no idea how bad it had been, when my parents e-mailed to let me know; I was too focused on my own successes and failures, wearing the rictus of my academic anxieties, handspanning my way through train timetables and subway lines and new cities and romantic hopes' playing out over London bridges, beside the Thames, through museums, in playhouses. I continued having no sense of the magnitude of this event until we went to Detroit during my surprise visit home for winter vacation and I saw my grandfather supine and still in an intensive care unit, metal rods clawing into his skull and into the halo stabilizing his head, protecting the encasement of the brain that would never let him be himself again. And even after I saw him in traction, weighted down, freighted with the force of an accident of which I think he was never fully aware, I didn't fully get it. And when, years later, a phone message arrived on my old answering machine, my father's voice announcing the death of my grandfather and telling me what time my flight would leave Ithaca for Detroit the next night so that we could have a weekend both of burying my grandfather's ashes (which my brother and I seem to have taken turns holding on our laps in the backseat of the car) and also of celebrating my grandfather's life, I think that I still didn't get it.

I don't know whether I ever cried over my grandfather's death. I know that I did cry over my grandmother's death, which was far more a shock, a suddenness that never closed, an event from which I didn't really recover, even as I didn't really sink into it. What happened with both of their deaths was that I started feeling their absences slowly, lengthily; my grandmother's death, in particular, has carved a hole in some of my most significant pleasures, a quiet desire that I could tell her or show her how things have turned out for me. She'd be worried about a lot of things, I suspect, but when my life turns well, I hear her voice in the back of my head, saying, "That sounds like it was real nice."

It is time for me, for now, to stop writing this prose elegy (which in some ways I didn't really get underway) for my furred friend, who used to resist eating his dinner until Plato, his long-gone compatriot, would bark and bark at him in his frustration, who lay on the floor under the table when I typed my grad school applications while taking care of him, who settled quiet in the office while I hashed out my senior honors thesis with one of his owners, who used to hold feet with me under the dining room table on Fridays, who used to come lie on the hard floor next to my end of the couch just so he'd be there when I wanted to lean over the side and pat him, who used to put his ears in my hands so I'd put my fingers in them (which no one else would do), who loved rice and broccoli, who could not even lift up his back legs to have their insides scratched by the time this summer started, who could barely get up from the hardwood floors these last two months, who nevertheless always came to the door to cry an always-worried hello when I, always worried, appeared to call him O Tohhhby sweetheart and pat his frame and rustle his ears and pluck out his undercoat and snap on his leash and sit on his bed with him through youth to seniority to decline. He was the son of Samson and Sheena. He turned fifteen in May. He was beautiful, and beloved, and the best of dogs. He was, as some friends of mine used to say, good people.

I am never there when the people I love leave; I think it's that grief that's smiting me today.

2 Comments:

While you were "not there" for those deaths, you were doing what you were supposed to be doing--living! That's what we're supposed to do, after all. We mourn for ourselves, for the loss we feel, for our sorrow. Still, though, without those sorrows we would not really understand joy. No matter how loved one--person or animal--is by us, or for how long, we cannot extend that life. We can only hope to bring to it joy and hope and comfort. I believe that's our purpose in our own lives.

Stop looking for the sorrow to "hit" you. It comes in its own quiet ways in soft times when we need to remember. It washes over us and through us and then moves on. So do we.

Our greatest sympathies. Please extend our sympathies to Toby's family for us. He was good people indeed.

Post a Comment

<< Home