Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Hot hot hawt.

The temperature goes up and up. Toledo tied its own record high (93, from 1962) yesterday. Youngstown broke its 1988 record (88) by one degree today. Once the rising day made it too uncomfortable to stay in bed reading any more Dickens or Virgil (the green sheets no longer crisp, the breeze no longer cool), I undertook two most difficult tasks: walking very slowly on my way to town through our humid-hazy, palpably thick afternoon, and cleaning my refrigerator. Every single food-stuff in my refrigerator at this moment is safe for consumption. Some of you will grasp fully just how triumphant I feel, being able to write those words. I was even going to take a picture for you, but I decided that that would be overkill, as it were.

While I could offer any number of hot-day reflections, I have houseguests tonight (with whom I'm road-tripping to my family and the deaf dog tomorrow, and then! Hem! on Thursday!). And so, rather than be rude to them by telling full-out stories now, I'll just leave some words to mark places in the backs of your heads for things I'll tell you later: Fla•Vor•Ice. Siestas (genius). Green percale. Heat drowsiness. Factory Gatorade.

And can I just tell you: my friends showed up tonight with a Making Fiends bumper sticker on their car. "Making Fiends!" I cried. Turns out they just received their t-shirts this morning, as they were leaving town. So now the three of us could go out in our Making Fiends shirts--and none of us would duplicate the others, for we have Giant Kitty, Vendetta, and Scissor Fiend among us. Delightful, truly delightful.

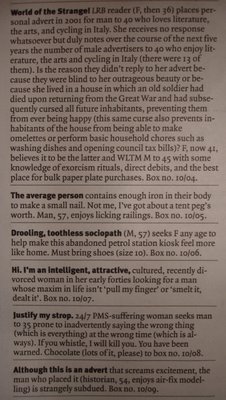

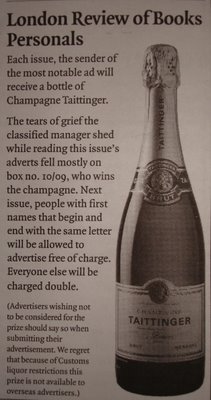

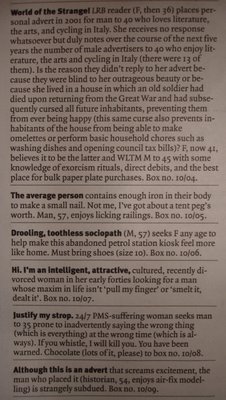

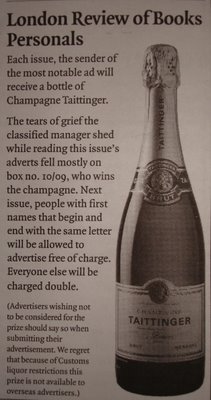

Because I'm not offering you much in the way of substantial reflection, here's the latest from the LRB (25 May). Once again, I think they've chosen the wrong winner. As always, click the images to enlarge them.

I'll wave at the Hell is Real billboards for you tomorrow; some of my student-athletes have told me that there are now four billboards in that sequence. Since I won't be driving, I might even be able to catch them for you. It will be my goal--nay, my duty--for the trip.

While I could offer any number of hot-day reflections, I have houseguests tonight (with whom I'm road-tripping to my family and the deaf dog tomorrow, and then! Hem! on Thursday!). And so, rather than be rude to them by telling full-out stories now, I'll just leave some words to mark places in the backs of your heads for things I'll tell you later: Fla•Vor•Ice. Siestas (genius). Green percale. Heat drowsiness. Factory Gatorade.

And can I just tell you: my friends showed up tonight with a Making Fiends bumper sticker on their car. "Making Fiends!" I cried. Turns out they just received their t-shirts this morning, as they were leaving town. So now the three of us could go out in our Making Fiends shirts--and none of us would duplicate the others, for we have Giant Kitty, Vendetta, and Scissor Fiend among us. Delightful, truly delightful.

Because I'm not offering you much in the way of substantial reflection, here's the latest from the LRB (25 May). Once again, I think they've chosen the wrong winner. As always, click the images to enlarge them.

I'll wave at the Hell is Real billboards for you tomorrow; some of my student-athletes have told me that there are now four billboards in that sequence. Since I won't be driving, I might even be able to catch them for you. It will be my goal--nay, my duty--for the trip.

Monday, May 29, 2006

Seventh up.

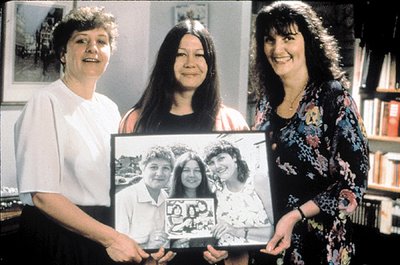

Jackie, Lynn, and Sue in 1992 (with pictures of themselves from 1985, 1978, and possibly even 1971), during the filming of 35 Up.

Jackie, Lynn, and Sue in 1992 (with pictures of themselves from 1985, 1978, and possibly even 1971), during the filming of 35 Up.I'll tell you, the best thing about the early days of the summer is feeling my mind open back up, after all those weeks of being trained on a series of tasks that absolutely had to get finished. By no means am I suggesting that they were loveless tasks; I am, by and large, a very happy, even ecstatic teacher, someone fully in her element while working with books and ideas and students and colleagues. But I ran into a former student on my way to dinner last night, and he e-mailed later to say, "You seemed unusually happy, so I imagine it had already been a good day," and I realized that the root of my having seemed happy was undoubtedly being well-rested and fully available to enjoy the evening.

This morning, having my mind free for now meant that when I ran into a banner ad in the middle of an article (and what the article was, I've now fully forgotten), hawking First Run Features's five DVD set of The Up Series, I was fully able to start some laundry, wash some dishes, and then sit down to rewatch 42 Up, the most recent installment in that series to have been released in the U.S. I remember reading about 42 Up when it appeared in 1999, though I didn't get a chance to see it until 2001 or 2002. (I can't remember now which summer it was when I became obsessed with trying to gather together all the Up films.)

And then I was able to decide to use some time this afternoon to introduce you to the Up series, in case you haven't run across it yourself. The films have been released in the U.S. since 28 Up, the fourth installment; 49 Up has already been out in Britain (it aired on television in September 2005) and is due to start appearing in the U.S. this summer (at the Seattle Film Festival, for instance), to show up in limited release October 6, and to come out on DVD November 14.

In 1964, Michael Apted was on a training course with Granada Television, based in Manchester, England. Granada's show World in Action decided to do a feature on fourteen seven year olds, in an attempt to see what England looked like through children's eyes, as well as what its future might be. The show's motto, borrowed from Frances Xavier, was "Give me the child until he is seven, and I will show you the man." After the first film's broadcast, Apted decided to do an installment every seven years, following these kids as they grew into adolescence and adulthood. Each installment has included substantial flashbacks to its predecessors, meaning that even if you've not seen any of the previous films, you can still appreciate and marvel at the richness of these people's accounts of themselves as they've aged through experiences both momentous and banal. The children were from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds: a few of the boys came from wealthy families and were attending posh schools; three of the four girls were from working-class families in East London, while the other attended a fashionable girls' school; a couple of the boys were from outside London (one from Liverpool, one from rural Yorkshire); one boy was the son of a West Indian father and a white mother. The questions have always been fairly simple: "Do you have any boyfriends?" "What do you think about girls?" "Is it important to fight?" "What do you think about rich people?" "What are you going to do when you grow up?" "What games do you play?"

In the initial program, the children go to a zoo together, and a somewhat droll voiceover explains the purpose of 7 Up:

This is no ordinary outing at the zoo; it's a very special occasion. We've brought these children together for the very first time. [droll chuckle] They're like any other children...except that they come from startlingly different backgrounds. [footage of one of the posh boys lecturing one of the others, who has just thrown something at a polar bear: "Stop that at once!"] We brought these children together because we wanted a glimpse of England in the year 2000. The shop steward and the executive of the year 2000 are now seven years old.It's an appropriately dramatic beginning; I'm imagining that 49 Up will kick off with the same line, only with "49" substituted for "42." Over the 42 years they've been profiled in Apted's films, these men and women have pursued a variety of educational and vocational tracks, some of which they confidently predicted even when they were seven; they've nearly all married, and some have been unfaithful to their spouses, and some have divorced; most have had many children. Their parents have died; they themselves have become ill; many have changed careers at least a couple of times. Their self-conceptions have shifted both subtly and dramatically over the years; they reflect in particular on Britain's class structures, on the possibility and mechanisms of self-improvement and social mobility, the social dynamics the program set out to explore in the first place. And several have dropped in and out of the program, citing various disagreements with it and with Apted (one man, for instance, agreed to participate in one installment but only if he could be interviewed by someone other than Apted). In a sense, for the fourteen of them, the program has itself become one of those conditions of life imposed in youth and only somewhat escapable in adulthood--one of the kinds of factors the program set out to explore and illuminate, in fact. Nick, now a professor of engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained to a reporter from The Chronicle of Higher Education in May 2005 (as filming for 49 Up was underway) how the program had affected him, commenting in particular on British accusations that he'd sold out by choosing to move to the U.S.:

[And then another voiceover comes in, as the World in Action theme music starts up again.]

In 1964, World in Action made 7 Up. We've been back to film these children every seven years. They are now 42.

I've got 42 years of history of this not being an easy process.... Maybe it is like family. However annoyed I am with them, you can't get around the fact that, when I was 6 years old, these people descended on me and put me on television. That, I'm pretty sure, made me think that there is more to the world than this tiny valley I'm living in. ... When they say it's surprising you didn't stay in this valley, well, they might be part of the reason.Now Playing Magazine's May 24 announcement that First Run Features would release 49 Up concludes with what its writer surely thought was a witty quip, suggesting that after the film's release, "all of the cast members will do their best to get on Survivor or Amazing Race, just to tide them over until 56 Up, of course." In fact, exactly the opposite is likely to be true: these men and women are, I suspect, the earliest reality television stars, and one of the reasons the Up series has never grown old (except, occasionally, for its sometimes-reluctant participants) is that Apted has stuck so faithfully to his original parameters. He conducts three-hour interviews and does some other miscellaneous filming with these men and women every seven years, then edits his hours of footage into the next installment of this collective auto/biographical portrait--a work woven together out of these men's and women's self-representations (and thus autobiographical) but held together with a guiding, third-person consciousness (and thus biographical). The only time Apted has broken his rules, by his account, it was to film the wedding of one participant, the ever-conscientious and thoughtful teacher Bruce; at the wedding, the participant with perhaps the most turbulent life, Neil, read a prayer he'd composed. The Up series, in other words, isn't about living for the camera. It's about a camera trying to catch life in an unobtrusive (though disciplined) way. This distinction is crucial; I'd even argue that it's what divides aesthetically and sociohistorically valuable reality television from dreck.

To be sure, the Up series has changed its participants' lives, as Nick's comment to the Chronicle has already suggested. When he filmed 42 Up in 1999, Apted asked the eleven who participated to tell him about how starring in the series had affected them personally. Nick laughed somewhat ruefully and said, "Well, we were talking about my ambitions as a scientist. My ambition as a scientist is to be more famous for doing science than for being in this film. But unfortunately, Michael, it's not going to happen." Andrew, a barrister, said, "If you came and asked me if you could do this to my children, I certainly wouldn't be enthusiastic. I think it's something that I wouldn't wish on someone, particularly." Jackie, now a divorced mother living in Scotland with her three children (and her rheumatoid arthritis, which I fear will have grown worse since 1999), explained the program's value to her: "I don't think I'd ever have kept a record of my life in the way that we have with this program. So, yes, I enjoy doing it. But it's not something that takes a great precedence." Suzy, a stay at home mother who has become a grief counselor, pointed out the dark side of that ongoing collective record: "There's a lot of baggage that gets stirred up every seven years for me that I find very hard to deal with. And I can put it away for the seven years, and then it comes round again, and the whole lot comes tumbling out again, and I have to deal with it all over again."

Seeing how Suzy deals with it all over again, whether Symon is still married to his second wife, whether Tony's still driving his cab, whether Neil is still hanging on to his mental health and his career in local politics, whether Bruce and his wife Penny are still happy, whether John and Charles have come back to the program--these are the things I'm looking forward to doing come November.

"What's the point of the program?" Charles asked when he was fourteen and still allowing himself to be interviewed. Nick may have summed up the Up series's point most cogently during his interview with the Chronicle, in the course of explaining why he's stayed with the series all these years, despite his reservations and discomforts: "Seeing people portrayed in time-lapse photography, you see things that you can't see otherwise.... It's insight into people. It gets to the heart of the people in some ways, if not all the time -- or even most of the time." The Up films suggest that life itself (not to mention the process of watching life) is like that last sentence: messy, inconclusive, self-contradictory, sometimes riddled with cliché, but eventually, in some small way, illuminated and illuminating.

sources for today's images: 1) the Director's Guild of America; 2) the 2000 Tampereen Film Festival's site.

Sunday, May 28, 2006

What if? What if?

In my dream, there were things I needed to do, more things, but what I wanted to do was sit and read a book. But there were more things to do, things I remembered after I'd started making plans to sit and read the book. What were these things? Were they things that I actually do need to do? Am I forgetting some task I promised to remember to complete? When I awoke and walked across the hall to the bathroom and looked out the window, checking for deer in the yard, and took my morning medicine and looked at my hair seeming to levitate above my ears, I thought with some relief that at least the dream had reminded me that I had to do these things--or else I would have sat on the couch with the book, possibly all day long. But in the ensuing ninety minutes, I've lost those things, if things they were, and now what I have is the restless edge of my morning coffee and a view of leaf-rustling breeze. And a cardinal in the tree, scarlet hopper. Some bird keeps running into my back windows, I think; occasionally this week I've heard a soft thump, at about the volume a mistaking bird would make. The cardinal hops from the tree to the roof, peers over, upside down, chirping percussively. And then he flies.

The dragon rematerialized yesterday.

Saturday, May 27, 2006

Tornado Warning #395.

This morning, I dreamed that the rain would not stop. It rained and rained and rained, water falling in thick ropy streams off my gutterless roof, until (looking out a window with my companion, whoever that person was) I said, "See how it rains? We're going to have a flood." Rapids were forming in my front yard. I was back in the house in North Vernon, the first Indiana house, standing at the window in my parents' bedroom, watching the yard fill with water, while the rain fell unceasingly. The rain would not stop.

Other things happened in the dream, things I may even have meant to tell you about, but that's the image that left a mark.

On Thursday evening, we had a tornado watch, and a thunderstorm so strong it bent my friends' forsythia bush over my car while we ate dinner and watched our movie and hockey game (or perhaps I should say: while we ate dinner and then my friends watched things and I fell self-flingingly into sleep and then did my bit to help my old dog friend to sleep, as well). When I arrived at the house, my friend was standing in front of her television and said, "There's a tornado warning." That last word, coming in instead of "watch," made everything different for me until I could confirm that the warning was in another county. "Tornado warning" is a phrase, I was reminded the other night, that mobilizes me, strips away every thought but that of preparing, descending, waiting, hoping.

For those of you who aren't from tornado-rich areas (like my students, who asked when the disaster siren went off at noon during our second week of class, "What should we do if it ever is a tornado?" and thereby earned themselves a lecture on tornado safety): A tornado watch means only that conditions are favorable for producing a tornado (whether suddenly or gradually). A tornado warning means that someone has spotted a tornado--it's in play and is being tracked and could be coming your way. In a tornado watch, one stays vigilant, checking the weather on a regular basis, recalling where to go in the building should something be spotted somewhere. In a tornado warning, one goes into a basement or, if there is no basement, into an interior space with no windows; the goal is to get as low and as centrally located and windowless as possible.

Now, I am known as something of a catastrophist in my family, I think; I have long been the one among us four most likely to believe that disaster is imminent and something to be taken seriously. I am the one, then, who noticed the weather icon in the corner of the television screen turn red and tornado-shaped, the day after Thanksgiving a couple of years ago, and I am the one who insisted we go to the basement, as soon as we confirmed that there was indeed a tornado warning on for my family's town.

It's possible that I would take tornadoes less seriously if I hadn't been schooled in them so rigorously by southern Indiana school systems. One of the first things I learned when I arrived in southern Indiana, midway through second grade, was what to do during a tornado drill; in fact, tornado drills were what I talked about when I visited my old class in East Amherst the next June. I demonstrated the position we all had to assume in the hall, into which we'd filed quietly and quickly: on the knees, facing the wall, head to the floor, textbook over the back of the neck and base of the skull. Avoid the hallways that are wind tunnels. Keep your eyes and mouth covered to protect yourself from broken glass. Get to the first floor, if you're in a multi-floor building. (I do not remember what we did in our nearly condemned junior high school, before my family left for a different town and district; I suspect I always believed that in a real tornado in that school, we'd all die, and thus any memory of our drills there have gone into the repression bin.)

In 1986, I read Ivy Ruckman's Night of the Twisters in conjunction with the Young Hoosier Book Award; even then, I was a sucker for books on lists. In 1985-6, I read nearly all of the YHBA nominees, on both the intermediate/elementary and advanced/middle school lists. In 1986, I must just have bought Ruckman's book from one of our Scholastic book order pamphlets; even then, I was also a sucker for buying more books than I'd planned to, always the kid with the biggest stack, always the one who bought the most discarded textbooks when the school sold them to us for $.25 apiece.

Night of the Twisters scared the bejeezus out of me, not least because of its vision of days without clean underwear. Why this particular detail should have bothered me so much more than the devastation of whole houses, I can only guess: I suspect it had something to do with knowing that, bereft of clean underwear (and, in turn but of less consequence to my ten-year-old self, of all other clean clothing), one would have to request such a very basic thing and thus would find one's dignity and personhood at the mercy of others.

That year, we watched a horrifyingly graphic tornado safety video in the school library. I also saw that tornado scene from Places in the Heart over and over again in the mid-1980s; I've never watched that whole movie, but I did learn from it that one should never accept a ride in a car from someone when the funnel cloud is bearing down.

Looming perhaps largest of all was the music video for Starship's "Sara," a song that plagued me in elementary school not least because of the video's traumatizing use of tornadoes. In this video, we get two narratives overlaid in farm somewhere on the plains, a location established with several Walker Evans wannabe shots of sturdy-looking depression-era farming family members, as well as some tractors and a barn, a tumbleweed and a dog. In the first, framing narrative, a tarted-up Rebecca De Mornay is running out on the massively mulleted lead singer Mickey Thomas in her red Chrysler LeBaron (or is that a Ford Mustang?) convertible. In the second, flashed-back narrative, a child (presumably the young Mickey Thomas, though this is chronologically confusing) loses an older woman to whom he is somehow affectionately bound, though it's never clear what their relationship is (is she his long-lost mother? is she an older woman on whom he has a childhood crush?). All we know is that she slides into this farming landscape in an enormous black sedan and sweeps him into her arms, and that later she rides off down their dirt road on a bicycle. And then that a tornado blows in and presumably kills her. The first, framing narrative is in color, the second in black and white, an obvious homage to The Wizard of Oz (whose tornado strangely never bothered me all that much).

The most disturbing thing about this video--even more disturbing than, say, the fact that Mickey Thomas may have fallen in love with the eponymous heroine of his video because she seems to be psychically tied to his long-lost older woman--is its double killing. For, at the very end of the video, as Rebecca De Mornay's Sara (who has vampily mouthed "I love you" in many home movie flashbacks during the video, before seeming to degenerate into a drunken party girl) charges off down the road in her convertible, the sky darkens and super-fake looking dry-ice-fog clouds come blowing in. She too will die in a tornado, we're left to believe. I think the lesson I was supposed to learn from this video, when I was ten, is that women should stay in their unobtrusive, unflashy places (and should never, ever cheat or leave)--or else they'll die in tornadoes.

Fortunately I didn't pay much attention to that part of the lesson.

The other thing I learned from seeing that video over and over again, though, is that tornadoes make an ungodly mess: the video features roofs being picked up and buildings being crushed by flying, falling objects. When it's all over, you can understand why everyone looks so stricken.

I suspect that the lack of a basement in the house in North Vernon was part of what always terrified me about tornadoes. We had a central closet where we probably all could have fit, and it was certainly windowless, but all we had under the house was a very shallow crawlspace. I ran into a difficulty somewhat like this one when I lived in Ithaca. There, I had a basement, but it was a good half-foot shorter than I, and it had a dirt floor and a significantly creepy feel. Horrors could have happened in that basement. I used to wonder whether I would actually have gone down into that basement, had we had a tornado warning while I lived there; there were windows in the basement, and it would have been one hell of a place to die.

By the time I lived in Ithaca, I had actually seen two tornadoes in person--except that they were out over a gulf and thus were waterspouts. That was the year I started packing a shoebox of possessions I wanted to be sure to have with me if a storm actually hit. Because I had just finished junior high (for we were on vacation that summer when we saw the waterspouts, which actually did significant damage not far from where we were), those possessions I deemed important were things like my Walkman and my favorite tapes, my deck of cards, a couple of key notes from important people, a small framed picture of the person I had had a crush on for months, a t-shirt, and clean underwear. I packed all of this stuff into the black and yellow Capezio shoe box my jazz oxfords (purchased for pipe organ lessons) had come in, and I had the box ready to go at a moment's notice, the second a warning hit. I think I packed a similar box for more severe-feeling tornado watches for the next couple of years. I don't remember what made me stop. I now know, of course, that clean water would be more important to me than clean underwear, and that it's absurd that flashlights were pretty much never in my emergency arsenal.

The amazing thing about the two waterspouts (which we saw on the same June day) was the way they focused and pulled water around. From shore, we could see the cloud of whipped water pouring upward at the spout's base; it looked like a symbiosis that could go on forever, this long, dark, grey chute tying and turning cloud to sea to cloud. I was so enthralled that I took pictures--or at least didn't protest when my father took pictures. Now, I'm not even sure whose pictures they were. But they were extraordinary, and it is indeed possible that my little camera was part of my emergency box, as well. You might not believe me if I tell you that the box didn't contain any books. But I think that it might be true; that was the year of making a half-hearted effort at being cool.

In the end, Thursday night's tornado warnings were three counties away and didn't threaten us at all, though I did learn this afternoon that one of my colleagues has a son who called her on Thursday from a neighboring college, where he was staying for a program, to ask what to do since he and his friends could see branches flying around outside; tornadoes touched down in that county, though fortunately not where he was. (She talked him through the tornado drill and he got everyone into the dorm basement. "I saved his life by remote control," she joked.) When the stormline reached us, the trees thrashed and dipped, and the rain pounded the ground and clouded the sky. We patted the dogs and waited for the power to go out. But the power stayed on, and the storm kept on going.

source for today's images: the NOAA (the first picture is the oldest known photograph of a tornado; it dates to August 28, 1884).

Friday, May 26, 2006

But where is my crew?

We're back in the midst of another eventful weekend here in Gambier; today marked the start of alumni/reunion weekend, and much of my day entailed getting ready, in some way or another, for tonight's reunion party for the study-abroad program my department runs (now in its thirtieth year). It's too early for me to have students coming back for reunions yet, and I'm in the anomalous position of being both an alumna of this program and a prospective director of it and someone too new in the department for any of the students (older or younger) to recognize. In a way, then, I was incognito just a bit, and that was mostly fine.

Now, graduate school was where I learned to party. Not until my third year in graduate school did I realize that people often go to parties with no estimated time of departure in mind; I had always shown up to parties with my excuse (almost always a need to do more work) ready to deploy within an hour. Ironically, the party that yielded my great revelation was also the one where I realized that I didn't have to like everyone--that I could admit, aloud, that I simply didn't like being around some of the people who had been at the party I was leaving. These twin revelations, in turn, helped me to choose which parties to attend and to plan on being at them for hours (though I am semi-famous for saying, "I'm only going to stay for a little while" and then closing places down).

Since leaving Ithaca, I have several times found myself in situations where, with my graduate school friends (particularly my crazy dancing friend), nothing would have been able to keep me from the dancefloor. I feel their absence most acutely at the annual event the senior class throws for faculty, in mid-February; the music blares, and people dance, but I simply can't bring myself (or couldn't this year, anyway) to get on the floor without my comrades in rhythm.

You can imagine the pleasure I felt tonight, then, when I looked around in hour three of our party and realized that I missed the colleagues who had been unable to join us. And then I wished for my graduate school friends, who are still (and will, I suspect, continue always to be) my favorite hepcat dancing partners. I suspect that this evening I may have made one of those microshifts, taken one more of those tiny steps that carry us from one part of life to the next, in a much slower and more gradual way than often gets acknowledged. I credit David Bowie and the Clash and Beth Orton and PJ Harvey with at least part of this realization.

Did I mention what a cool party we threw? We have the leftover cheese--enough, as a friend of mine put it, to make a thirty-two-cheese omelet for breakfast--and cases of beer and wine to prove how ready we were. And this, in turn, means there's more coolness to come.

Now, graduate school was where I learned to party. Not until my third year in graduate school did I realize that people often go to parties with no estimated time of departure in mind; I had always shown up to parties with my excuse (almost always a need to do more work) ready to deploy within an hour. Ironically, the party that yielded my great revelation was also the one where I realized that I didn't have to like everyone--that I could admit, aloud, that I simply didn't like being around some of the people who had been at the party I was leaving. These twin revelations, in turn, helped me to choose which parties to attend and to plan on being at them for hours (though I am semi-famous for saying, "I'm only going to stay for a little while" and then closing places down).

Since leaving Ithaca, I have several times found myself in situations where, with my graduate school friends (particularly my crazy dancing friend), nothing would have been able to keep me from the dancefloor. I feel their absence most acutely at the annual event the senior class throws for faculty, in mid-February; the music blares, and people dance, but I simply can't bring myself (or couldn't this year, anyway) to get on the floor without my comrades in rhythm.

You can imagine the pleasure I felt tonight, then, when I looked around in hour three of our party and realized that I missed the colleagues who had been unable to join us. And then I wished for my graduate school friends, who are still (and will, I suspect, continue always to be) my favorite hepcat dancing partners. I suspect that this evening I may have made one of those microshifts, taken one more of those tiny steps that carry us from one part of life to the next, in a much slower and more gradual way than often gets acknowledged. I credit David Bowie and the Clash and Beth Orton and PJ Harvey with at least part of this realization.

Did I mention what a cool party we threw? We have the leftover cheese--enough, as a friend of mine put it, to make a thirty-two-cheese omelet for breakfast--and cases of beer and wine to prove how ready we were. And this, in turn, means there's more coolness to come.

Thursday, May 25, 2006

He was not there for long.

Dragon watch: I took this picture yesterday afternoon; today, he is already gone. Alumni are returning to campus tonight and tomorrow; I can only hope that no one takes too much of a shine to my small friend, if he even turns up again in the next few days.

I think the cats at the dragon's house are actually starting to watch for me, now that they know I pass by and will even (despite allergies) stop and play with them. Sometimes when I go by and say hello to one of the three cats, if one is out, the other two will stand up on their back legs and brace themselves on the front door with their front paws and peer out at me.

What I want to tell you about tonight is Tornado Watch #395. And yet sleep is storming me, which means I'll have to write about meterological cataclysm tomorrow.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Takeaway.

An evening of struggling with Powerpoint has made me dislike that program even more than I did before; everything seemed good until the slideshow that took me three hours to construct suddenly started crashing the program. Repeatedly. Just when I was about to give up and start over, everything started working again, but I don't feel particularly reassured that this mishap won't recur. The whole experience reminds me of the time my first graduate seminar paper somehow got itself corrupted (I swear there was no operator error involved with this file's demise) the morning I was due to leave Ithaca for winter break. Since I had three hours before I had to depart for the airport, I decided that I would simply retype the entire paper--all 28 pages of it. With footnotes. I made it through about 24 before I had to admit defeat and pack all my dirty clothes into a suitcase and all my sleepless, unwashed self into my winter coat for the trip home. At least this evening I can chart how far I've come since those panicky days. On the other hand, this slideshow isn't for a grade; it's for this weekend's reunion of participants in Kenyon's study abroad program at the University of Exeter in southwest England.

I was tossing around plans to write about something else today, but all the effort I've been expending on the 150 images in this slideshow has left me thinking instead about living and traveling in England. It's been an even decade since the end of my stay there; ten years ago today, I was almost certainly doing what the English call "revising," or studying for the exams that made up the bulk of my year's grades. Revising for exams was a particularly interesting experience for me, since it was during my Exeter year that I learned how much more effectively and happily I could work if I didn't force myself to work all the time, as though reading and taking notes were my only reasons for being.

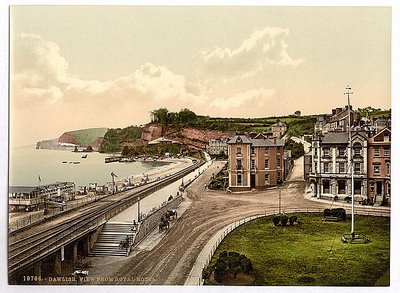

One of the things I learned to do during that year was to use my weekends to take trips, particularly around Devon, the English county in which Exeter is located. In early March, for instance, I traveled with my Londoner flatmate by train to the coastal resort town of Dawlish, about ten miles from Exeter. Devon's south coast features a number of seaside towns oriented toward vacationers. (One, Torquay, is even called the English Riviera because of its very temperate climate and abundant sunshine; Elizabeth Barrett Browning went there to recover her health in the 1830s, only to have her beloved brother drown there in 1840.)

One of Dawlish's claim to fame is its seaside railway line, designed by Victorian engineering giant Isambard Kingdom Brunel in the 1830s and completed in 1846 (follow that link to see one of my favorite photographs). On my first trip to Dawlish--to see a touring production of The Tempest late one January night--I had had to take a bus with my classmates because bad rains and high seas had flooded the Great Western Railway's coastal line. Even from the highway, we could see how close the sea was to the tracks. In fact, last October, a professor from the Devon Maritime Forum who directs the University of Plymouth's Marine Institute warned that an increase in coastal storms, as a result of global warming, will pose a growing threat to this really stunning stretch of rail. The line's getting overtopped by winter storms is bad enough, he argued, but the really devastating prospect is that the whole line could simply get washed away by a really severe storm, thereby cutting off the southwest of England's rail links to London and threatening the region's economy. In case this warning sounds overly dire, take a look at this image of a wave hitting the train on a sunny day:

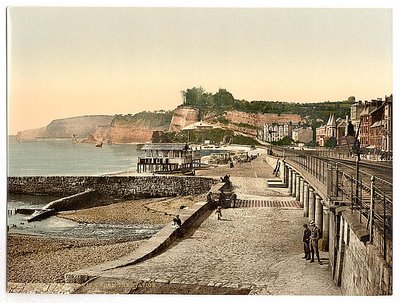

By the time my flatmate and I traveled to Dawlish, the rail lines were open again. We disembarked right where the train is stopped in this image (what you can't see in this picture is that the tracks are elevated above the beach, atop a seawall; you can get a better sense of the tracks' spatial relationship to the beach and to the town of Dawlish if you look back at the image with which tonight's post begins). The weather was grey and a bit gloomy, though fairly warm given that it was early March. I don't remember what we did first when we arrived in town. I do remember that we climbed up into hills west of town--the green hills atop the red sandstone cliffs in that first image--and that it drizzled a bit while we were wending our way toward whatever vista we could find. One of the extraordinary things about England, in case you've never been, is its plethora of public walking paths; it's much, much easier to roam about in the countryside legally than it is in this country, not least because of public footpath signs that show you where to veer off of the pavement and into a field. The vistas we found that day were the ones to which my mind flew when I saw Marianne Dashwood running over green Devonshire hills in Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility a month later.

The thing I remember most clearly about that March day in Dawlish is, I think, the thing that happened first: we bought ourselves lunch at what is to this day my favorite fish and chips takeaway anywhere, a small shop just across the road from the railway tracks, at the edge of Dawlish's town center. From some searching around, I think I've ascertained that the place was called Tuckaway. I know that I could walk straight into the shop, if someone put me down in Dawlish and told me to get myself there. Tuckaway's fish and chips were only available for takeaway: you got your white paper tray of freshly fried chips, topped with your freshly fried slab of plaice, the whole thing wrapped twice in white butcher paper. I think that the chips were even salted (and possibly also vinegared, if you requested that, which I certainly did) before the fish went over them. Your only utensil was a wooden fork highly reminiscent of those miniature tongue suppressor spoons we used to get with our ice cream cups in elementary school. The whole deal cost about £4. My flatmate and I took our heavy, aromatic, soon-to-be sodden bundles of food across the road, under the train tracks, and out to the beach. Basically, we emerged on the beach side of the sea wall at right about the place where the two swells are standing in this picture

and we proceeded to hunch over our hot half-unwrapped pounds of fish and chips somewhere along the seawall, probably about where the child is perched on the wall there.

and we proceeded to hunch over our hot half-unwrapped pounds of fish and chips somewhere along the seawall, probably about where the child is perched on the wall there.Rarely in my life have I taken such pleasure in the first taste of a food as I did that afternoon on the Dawlish seawall. (I would put the time I ate fried calamari and drank retsina late one July night at a seaside taverna in Naxos up against that moment, but not many others.) Tuckaway's fish were perfect--their batter crisp, their interiors moist and soft--and their wide-cut fries were simply divine, like some Platonic ideal of french fries (if that were how Platonic ideals worked). We ate greedily for a few minutes, pausing only to exclaim (with our mouths full) over how very good indeed this meal was. And all was well, until we realized something crucial: we were nearing surfeit, and consequently we were starting to find our meals repulsive. We pushed on and, I think, actually ate everything in our butcher papers. But then we needed to walk around--which is part of what makes me suspect that we ate right away and then wandered the beach, trying to get near the sandstone arches that reach into the sea west of town, and then wandered up into the hills, trying to get a view of those arches from above. (I later realized that the only real way to see the arches is to take the train further west than Dawlish.) And I couldn't think about eating more Tuckaway takeaway for several months.

By June, though, I was ready for more. On the summer solstice, when the dawn came before 4 a.m., I had had my first real date with the person to whom my heart had devoted itself much earlier in the year. A few days later, on a day that dawned sunny and warm, our teacher (now the excellent friend who feeds me on Fridays and with whom I'm going on a cheese-buying adventure tomorrow) told my new somebody that he and I should knock off the work and enjoy our last few days in England. And so we did, and how: we ventured to the local Tesco to buy strawberries and then hopped the train to Dawlish and spent the day at the seashore. One of the first things we did was buy lunch at Tuckaway.

What I remember most clearly from that day: how very many people were out walking the streets of Exeter before we caught that train. It was so warm, so sunny, so very mid-June that it seemed everyone had simply walked off the job, out of school, out, just plain out, and everyone was sunning, everywhere. I think I wore a blue shirt. I know that my chin was chapped from mad evenings of ardent kissing; all day, I was so self-conscious about how legible my body had become and could not stop fingering my raw, scaly chin. I know that we spent the better part of the afternoon skipping stones into the English Channel, because this somebody was the one who had taught me to skip stones, up in the Lake District two weeks earlier. I know that we missed our train and decided just to walk eastward along the beach to the next station, at Dawlish Warren, and that somehow--because the temperature was plummeting, I think--we ended up taking shelter (and ordering Pepsis) in the local resort, where strange things seemed to be afoot.

And I know that I have never had better fish and chips.

sources for tonight's images: U.S. Historical Archive; British Conger Club;

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

The soundness of night birds.

What is thought, after all, what is dreaming, but swim and flow, and the images they seem to animate?

At 9 p.m. the sky had developed its lightly incandescent evening blue, so I walked into my red shoes and out of the house. Stepping along down the night street, I was struck above all things by the myriad sounds of innumerable birds--jays, robins, starlings, cardinals, and all the others I could not see and cannot name. A tiny sparrow (a chipping sparrow, I think) jumped from child oak tree to child oak tree, keeping one tree ahead of me all the way down one short street, its tiny head, reddish brown (they call it rufous), giving it away as it flickered in the leaves. The lights on Middle Path are back on this week; they came back on for commencement and will stay on in the evenings until our upcoming alumni weekend concludes. It's a strange effect, the illumination of the path by white lights even before the sky is fully dark, even before stars have a chance to make themselves seen. It's a stranger effect if one walks the path's gravel recalling the bone-chilling cold in which one photographed these same trees, this same path, five months ago.

The birds chirruped and called and dashed and dipped on as I mused on my memory's multilocality, until one last sound set me looking for its source. A Canada goose's honk will arrest me in my tracks any time, but particularly at times when I expect the geese to be settling, tending goslings, resting up for the next migration. (In my fantasies, they are still wild, not suburbanized and industrialized and making do with puddles and retention ponds.) But here, in the early night, were geese calling to one another, flying somewhere out of sight but, I gathered from their sound, below the treeline. I stood in the road--it is possible once again, for this present short time, to forget oneself in the middle of a road without harm--and peered to the north until one, two, three silhouettes slipped by against a shard of night blue. The honks continued, intermittent, and I stood, stopped.

-- Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping

At 9 p.m. the sky had developed its lightly incandescent evening blue, so I walked into my red shoes and out of the house. Stepping along down the night street, I was struck above all things by the myriad sounds of innumerable birds--jays, robins, starlings, cardinals, and all the others I could not see and cannot name. A tiny sparrow (a chipping sparrow, I think) jumped from child oak tree to child oak tree, keeping one tree ahead of me all the way down one short street, its tiny head, reddish brown (they call it rufous), giving it away as it flickered in the leaves. The lights on Middle Path are back on this week; they came back on for commencement and will stay on in the evenings until our upcoming alumni weekend concludes. It's a strange effect, the illumination of the path by white lights even before the sky is fully dark, even before stars have a chance to make themselves seen. It's a stranger effect if one walks the path's gravel recalling the bone-chilling cold in which one photographed these same trees, this same path, five months ago.

The birds chirruped and called and dashed and dipped on as I mused on my memory's multilocality, until one last sound set me looking for its source. A Canada goose's honk will arrest me in my tracks any time, but particularly at times when I expect the geese to be settling, tending goslings, resting up for the next migration. (In my fantasies, they are still wild, not suburbanized and industrialized and making do with puddles and retention ponds.) But here, in the early night, were geese calling to one another, flying somewhere out of sight but, I gathered from their sound, below the treeline. I stood in the road--it is possible once again, for this present short time, to forget oneself in the middle of a road without harm--and peered to the north until one, two, three silhouettes slipped by against a shard of night blue. The honks continued, intermittent, and I stood, stopped.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Is this the one where he falls in love with the devil?

When I watch television, I like to guess what's coming next in a narrative. I know I am not the only one. In my family, correct guesses lead to someone's saying, "Did you write this one?" I also enjoy racing my friends and family, trying to be the first one to call an episode that we've all seen. Tonight, while I was watching an exceedingly strange show at my excellent friends' house, one of them said, "Wait, is this the one where he falls in love with the devil?" I was tickled. There it is.

The grading out of the way, today became a day of slow walking and picture-taking. There were the flowers in town, yet another new round blooming, yellows and pinks and whites (and soon there will be coneflowers--not really soon, but soon, now that there's yarrow that will soon be as yellow as that curb):

And the dragon has moved yet again--not disappeared, just moved. But when I paused to contemplate whether or not I'd photograph him where he is now, the high-mewing cat who lives at the dragon's house (or at whose house the dragon lives) came out for a visit. Playing with this cat, trying to photograph her as she slinked around and meowed happily at me (don't let the vampiric incisors fool you) and then started eating grass, was one of the highlights of the day. Since I need at least one good night's sleep to get my equilibrium back, and since I'm just so tired from my push to get those grades in, I think I'll mostly let these images speak for themselves. Trust that you'll hear more from me tomorrow. When do you ever not hear more from me?

Walking the quiet distance home (for the students are gone; we are hushed and emptied out for now) and encountering the cat all reminded me, suddenly, of Ithaca--of how evening walks through Fall Creek meant overhearing house noise, people playing piano or clinking silverware to plates during dinner or conversing on porches. Of how cats would wander the sidewalks before the houses where they lived, and of how they would topple onto their backs and roll back and forth, stretching and scratching their spines against the cement, when they saw me approach. Some nights, especially when I was writing, I would walk out of the house at 8:30 or so and just walk for awhile, often ending up at one of the bookstores downtown. One Monday night, someone tried to get me to join in the contra dance taking place on the Commons. I flushed shyly, as is my wont when approached with anything like interest, and hurried home to sit with a paragraph I couldn't quite solve.

One night, I looked up to see a bit of graffiti painted in white on a brick wall, high above the street: "When home is rootbound."

This cat has the highest, most improbable mew I've ever heard, which is saying something, as you'd know if you'd known the cat we had when I was little.

The grading out of the way, today became a day of slow walking and picture-taking. There were the flowers in town, yet another new round blooming, yellows and pinks and whites (and soon there will be coneflowers--not really soon, but soon, now that there's yarrow that will soon be as yellow as that curb):

And the dragon has moved yet again--not disappeared, just moved. But when I paused to contemplate whether or not I'd photograph him where he is now, the high-mewing cat who lives at the dragon's house (or at whose house the dragon lives) came out for a visit. Playing with this cat, trying to photograph her as she slinked around and meowed happily at me (don't let the vampiric incisors fool you) and then started eating grass, was one of the highlights of the day. Since I need at least one good night's sleep to get my equilibrium back, and since I'm just so tired from my push to get those grades in, I think I'll mostly let these images speak for themselves. Trust that you'll hear more from me tomorrow. When do you ever not hear more from me?

Walking the quiet distance home (for the students are gone; we are hushed and emptied out for now) and encountering the cat all reminded me, suddenly, of Ithaca--of how evening walks through Fall Creek meant overhearing house noise, people playing piano or clinking silverware to plates during dinner or conversing on porches. Of how cats would wander the sidewalks before the houses where they lived, and of how they would topple onto their backs and roll back and forth, stretching and scratching their spines against the cement, when they saw me approach. Some nights, especially when I was writing, I would walk out of the house at 8:30 or so and just walk for awhile, often ending up at one of the bookstores downtown. One Monday night, someone tried to get me to join in the contra dance taking place on the Commons. I flushed shyly, as is my wont when approached with anything like interest, and hurried home to sit with a paragraph I couldn't quite solve.

One night, I looked up to see a bit of graffiti painted in white on a brick wall, high above the street: "When home is rootbound."

This cat has the highest, most improbable mew I've ever heard, which is saying something, as you'd know if you'd known the cat we had when I was little.

Sunday, May 21, 2006

Time, time, time: see what's become of me.

While I waited in yesterday morning's line-up, before our commencement procession began, I looked down and discovered a scrap of paper on my campus's central walkway, the one-mile stretch of gravel called Middle Path. The sun was dapply, the light wind cool, the very air lively with pride and expectation (not least because of the prominence of our commencement speaker). And once everything got underway, it all flew past like the birds I spend so much of my time watching: the speeches, the diplomas, the singing, the congratulations, the embraces. And the departures, so many departures.

So I photographed the scrap of paper, and you can click on it for a better view.

My semester isn't quite over; I'm now finishing that grading that got put aside when my anticipatory tears started falling late last week. Somewhat mercifully, I found myself completely dry-eyed at our two days' worth of ceremonies. In the pictures, I'm looking on with a proud smile as speaker after speaker and student after student files past. In my favorite photos from the commencement ceremony's aftermath, my students are the ones looking at the camera being wielded so ably by my brother the photographer, while I watch them watching themselves being captured. In a couple of pictures, I think I can trace the beginnings of new phases of friendship and correspondence; in the best ones, I'm laughing with these men and women--my students no longer--over jokes that I suspect were hilarious at the time but that I cannot remember even a day later.

And so, you see, it's not just because of the grading left to finish that I've found myself musing on the title of the book that lost its original circulation card on Middle Path--and, despite myself, feeling as though I too might be a scientist against time. If you knew these men and women, you wouldn't want them to leave you, either, though you'd also want them to make the most patient, attentive, and thoughtful haste toward the tremendous lives awaiting them. They are so young. They are not so much younger than I. So much will happen to and for them now. When next I see some of these young men and women, they will be married; at least one will probably have a child already. Some will be single and happy; others will be single and desperate; some will be doing fabulously fulfilling work; some will already be changing careers. Some will still be figuring out what the hell they're doing in every arena in life. They'll be artists, thinkers, writers, editors, friends, spouses, partners, parents. Importantly, I hope, they'll still be their own inimitable selves, still growing, still nosing around, still wondering why and asking how.

I have spent the interstices of my grading day hoping that I did my part of preparing them as well as I tried to do it. Did I help install the question mark at the ends of their thoughts, so that they'll never rest too easily in anything they're told? Did I help stoke their love of books and ideas and discussions, a love fierce and tenacious enough that they won't let the relentlessness of everyday life sidetrack their intellectual passions? Did I help them see inside the lives of words? Did I show them how much it matters to be careful with and for other people? Will they be happy? Will they be good? Will their worries be soft and their burdens manageable?

And under how many of these questions rankle the ones I can't ask--not of them, not of anyone. Will they miss me? Will I exist for them when they're here no longer? On one hand, I know the simple answers to these questions. But on the other hand, I don't and won't know, and maybe no one will really ever be able to tell me.

(But no. After a night's sleep: if you knew these men and women, you would, as I do, want them to go away, without regret and without nostalgic weight. And you'd want them to return occasionally to report on what they've seen. And you'd know that some will, and you would be happy with that, and you'd be able to remember today that you're actually a scientist of time, not against it. You would perhaps also have to acknowledge that you are ambivalence's own anatomist.)

So I photographed the scrap of paper, and you can click on it for a better view.

My semester isn't quite over; I'm now finishing that grading that got put aside when my anticipatory tears started falling late last week. Somewhat mercifully, I found myself completely dry-eyed at our two days' worth of ceremonies. In the pictures, I'm looking on with a proud smile as speaker after speaker and student after student files past. In my favorite photos from the commencement ceremony's aftermath, my students are the ones looking at the camera being wielded so ably by my brother the photographer, while I watch them watching themselves being captured. In a couple of pictures, I think I can trace the beginnings of new phases of friendship and correspondence; in the best ones, I'm laughing with these men and women--my students no longer--over jokes that I suspect were hilarious at the time but that I cannot remember even a day later.

And so, you see, it's not just because of the grading left to finish that I've found myself musing on the title of the book that lost its original circulation card on Middle Path--and, despite myself, feeling as though I too might be a scientist against time. If you knew these men and women, you wouldn't want them to leave you, either, though you'd also want them to make the most patient, attentive, and thoughtful haste toward the tremendous lives awaiting them. They are so young. They are not so much younger than I. So much will happen to and for them now. When next I see some of these young men and women, they will be married; at least one will probably have a child already. Some will be single and happy; others will be single and desperate; some will be doing fabulously fulfilling work; some will already be changing careers. Some will still be figuring out what the hell they're doing in every arena in life. They'll be artists, thinkers, writers, editors, friends, spouses, partners, parents. Importantly, I hope, they'll still be their own inimitable selves, still growing, still nosing around, still wondering why and asking how.

I have spent the interstices of my grading day hoping that I did my part of preparing them as well as I tried to do it. Did I help install the question mark at the ends of their thoughts, so that they'll never rest too easily in anything they're told? Did I help stoke their love of books and ideas and discussions, a love fierce and tenacious enough that they won't let the relentlessness of everyday life sidetrack their intellectual passions? Did I help them see inside the lives of words? Did I show them how much it matters to be careful with and for other people? Will they be happy? Will they be good? Will their worries be soft and their burdens manageable?

And under how many of these questions rankle the ones I can't ask--not of them, not of anyone. Will they miss me? Will I exist for them when they're here no longer? On one hand, I know the simple answers to these questions. But on the other hand, I don't and won't know, and maybe no one will really ever be able to tell me.

(But no. After a night's sleep: if you knew these men and women, you would, as I do, want them to go away, without regret and without nostalgic weight. And you'd want them to return occasionally to report on what they've seen. And you'd know that some will, and you would be happy with that, and you'd be able to remember today that you're actually a scientist of time, not against it. You would perhaps also have to acknowledge that you are ambivalence's own anatomist.)

Saturday, May 20, 2006

Friday, May 19, 2006

Like a dragon in the sun, we'll be playing and having fun.

It is not sunny here, alas, for the kick-off of our formal commencement celebrations. And though my graduators don't read these writings, I'm going to put up the dragon--in his sunny glory from yesterday evening!--as a talisman for their festivities. For at least a couple of reasons, the dragon may be all you'll get from me today, though one never does know.

Thursday, May 18, 2006

Leaving the nest.

Today, I've really been feeling the fact that some students of whom I've become very fond won't be here anymore, after a couple more days. I've spent a lot of the day roaming about, doing some errands, continuing my always fruitless search for the perfect special events lipstick (tonight's story for another time), spending some time with my excellent friends. Tomorrow, our ceremonies start, and once they're underway, we're on the fast track to a relatively quiet, depopulated Gambier.

My father has sent me the perfect pictures for the way things are today. I think that I'll refrain from even offering commentary, other than to tell you that these geese live at the factory where he's working near Chicago this week. You can imagine your own captions and connections, though those captions and connections will be much funnier and probably more poignant if you know the pomp and procession of a certain kind of small college's graduation ceremonies.

The funny thing about goslings is that their feet give them away, reveal them as the creatures they'll be when they get much bigger.

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

Such loud darkness.

Remember how I told you that I live in a thunderstormy area? This evening, a noisy front is pushing through the county, and it took the power out about ninety minutes ago. One moment, I was talking with my mother; the next, I was conversing with white noise. I groped my way to the flashlight, thankful as ever that my memory is sharp with details like where the flashlight randomly got stowed the last time I used it (not in a logical place, I should perhaps add). I lit my way to a couple of candles. I set myself up for some reading, then realized that in the candlelight, my head was throwing an enormous shadow on the wall over my right shoulder.

Seven (slow-going, because I'm tired) pages of Housekeeping later, the electricity came back to the house. But the outage has, I think, done its part to sap the rest of my own current away for the night.

And so, two things, and then I'm departing, disembarking for another night of dreaming, perhaps.

First: when I peeked out the bathroom window this morning to see whether anything interesting was happening in the yard, I was startled to see three large, richly red deer in my backyard--reclining in a group, munching and mawing and resting together. They saw me when I padded barefoot into the kitchen to make the coffee I'd take back upstairs to bed. Within ten minutes or so, they stood up and wandered away; I caught a glimpse of only one of thier tails.

Second: here are the kinds of passages I live for, from Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping:

But the lake at our feet was plain, clear water, bottomed with smooth stones or simple mud. It was quick with small life, like any pond, as modest in its transformations of the ordinary as any puddle. Only the calm persistence with which the water touched, and touched, and touched, sifting all the little stones, jet, and white, and hazel, forced us to remember that the lake was vast, and in league with the mood (for no sublunar account could be made of its shining cold life). (112)Now we're in a sonic lull: the rain has stopped, as have the flash and rumble of this May shower.

[W]hy must we be left, the survivors picking among flotsam, among the small, unnoticed, unvalued cluter that was all that remained when they vanished, that only catastrophy made notable? Darkness is the only solvent. While it was dark...it seemed to me that there need not be a relic, remnant, margin, residue, memento, bequest, memory, thought track, or trace, if only the darkness could be perfect and permanent. (116)

This afternoon, while I mowed the lawn, I discovered whole bushes of fat peony buds, round and taut like little rubber bouncing balls, and those bushes are pushing out toward the light, emerging from their surrounding hedge. I thought yesterday's peony a completely isolated renegade. Now, happily, it looks as though I misjudged.

Turns out Ohio is one of the top ten states in the country for lightning casualties.

source for tonight's image: the Electricians' Toolbox page promoting lightning protection.

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Concatenation.

This morning, in the hour before the alarm rang, I dreamt that I learned I was pregnant. In the dream, I was traveling, both on some sort of journey with a group of people (who may have included my family) and also on my own rambles just beyond the expected parameters of that group's movement and stasis. At some point, I saw a map, and on that map, near the end of a spit of land, was the label "Dr. S." "A place named for me!" I exclaimed to someone in the dream. Strangely, I kept wandering, and at high speed, and the news of my pregnancy only complicated and intensified my desire for motion, my need to keep tracing long ovals through a rural landscape that echoed southern Indiana and mid-Ohio without ceasing. Except on the map, where everything was pure coastal fringe, water fingering coastline, interlocking saltwater and sand. The pregnancy concerned me, even in the dream: I remember trying to recalculate the flexible spending account I create with paycheck withholdings every month, thinking that it was terrible that I'd just underestimated what I'd need, only days before learning that I'd probably be spending thousands on prenatal care.

The dream itself was a sign of burgeoning, of things simmering and percolating and concatenating--all those metaphor-mixing verbs. Saturday's commencement ceremony is a massive beginning anew for the students, of course--a beginning again as non-students--but today I'm far more focused on the ways that the close of an academic year represents the rebirth of all those parts of my scholarly identity that get displaced ever so slightly by the day-to-day work of teaching and advising. An alternate set of books has been gravitating to my bags and desks this week, following me around along with the final grading I tote about. (And have I never told you that my main workbag is actually a diaper bag? That's another story altogether, as usual.)

Part of what yielded my dream of impending nativity: at a reception last night where I had a chance to interact with one of my favorite local babies, I was startled that--as I played with this child--an older friend whom I haven't seen for awhile called out to me, "No, no, not yet," obviously instructing me not to have a child now. I had never realized the degree to which being told not to reproduce could feel just as intrusive as being asked when I planned to reproduce. (I count myself blessed that no one actually asks me this question, that instead I hear about others' being asked it.)

Another part of what birthed the dream: I had a major meeting this morning to discuss my work, and while I had no real fear that the meeting would be anything but insightful, supportive, and even provocative, I can freely admit to having felt the tiniest squeeze of anxiety. The dream's suggestion bore fruit, though: the meeting was not only reassuring but even generative: I've bumped one of my major professional goals forward by about six months, a move that feels scary and invigorating all at once.

This afternoon, I was having coffee with my excellent novelist friend. We took advantage of the rain's having stopped--a cessation that continued through the afternoon and even brought with it some sun, so welcome--by sitting outside the coffeeshop. About halfway through our time out there, a cement mixer passed by, its tub spinning and spinning, as they do, always. As we walked back to the officehouse, the truck passed us going in the other direction, and I mentioned my childhood love of those trucks (and found out that his daughter loved them, too--why should this be? we wondered, deciding it might have something to do with the multiple axes along which those trucks' circular motions happen simultaneously). As a kid, I was in love with medium-sized trucks: the UPS truck; the garbage truck; and especially the cement mixer. For the hell of it, I'm going to force the analogy: it's possible that one reason the cement truck looked right and important (or right important) to me today lies in the fact that I'm continuing to embody this alternate kind of gestation process, even if only for myself, and that the closing of the semester and the opening of the summer form one of those transition points where I become more fully aware than before of all the growing and tending and nurturing I've been doing, in hidden places and at barely known times, even at my busiest moments this semester. This alternative, repetitive motion has kept going even as I've been moving straight on ahead; the stuff that needs to stay in the mix has stayed in the mix, and it's nearly time to see what's in there.

And then I slip effortlessly back to the organic analogy, because a spinning truck will only take me so far. Greening, I keep thinking to myself these days. It's all greening. I'm greening. And oh, just you wait. Just you wait and see.

Monday, May 15, 2006

Washing out.

The rain keeps falling. Just before lunch, I espied these brilliant orange flowers. At first, I passed them by, figuring I'd photograph them later. Then I realized that the rain could start again at any second. I turned around and shot these closest things to bright sunshine I've seen in days. And sure enough, by the time I was done eating lunch, it was pouring.

Flooding isn't in our forecast, and Gambier lies up a hill from the river anyway. But it feels as though the rain pouring on us is flushing out our light and lots of our colors (though not our greens, which are more vibrant than ever).

As evidence of how washed out we're getting, witness the sodden dragon.

Granted, he would seem sharper and less washed out if I hadn't ended up photographing him late in the evening again. But my least favorite effect of continuous rain is that all through the day the light never gets stronger than that of late evening.

A postscript to yesterday: I got home late this evening, after dinner and another round of grading, to find a phone message from my mother--who said, among other things, "I can give you a hint about what your next quilt will be..." That's what I forgot to tell you: the most magic thing about my mother's quilts is that they just keep on coming. She keeps on making them. She keeps on giving them to me. I have a whole legacy of her work with fabric, a whole textile tale of my life as her daughter. Seriously: when I stopped by to see her as a surprise one Sunday night last fall, she sent me back to Gambier the next morning with a new quilt. I did nothing to deserve her as my mother, but I sure am glad we ended up together.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

Red hot mama.

My mother and I traveled to Boston's Museum of Fine Arts last summer to see an exhibit of quilts from Gee's Bend, Alabama. The Gee's Bend quilts had shown at the Whitney in New York City in winter 2002-03 and had been on the road pretty much ever since, as far as I knew. We managed to make it to the show on the day of a gallery talk, and so we visited the quilts twice: once in the morning, just after the museum opened, when we knew we'd have ample time to wander around, separately and together, examining the stitching and the patterns close-up and from afar. After our first couple hours of looking, we headed down the road to the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum (a story for another night), but we went back to hear the docent's talk.

Not surprisingly, the talk was packed. Having done some docent work, my heart sank for our poor speaker, who had to find a way to move sixty people through galleries and still be heard. Her strategy, logically, was simply to park us in front of a few pieces and talk from there. Midway through her first quilt, the docent asked for questions, and a woman in the front row started trying to assert some kind of authority by talking about having met the quilters when they traveled up from Alabama for the show's opening. She praised them for having really had a sense of themselves as artists, not just as women who happened to have made quilts. And just when things started sounding as though they were going to get really condescending--these simple women from Alabama somehow became great, if somewhat unconventional, American artists! almost despite themselves!--my mother raised her hand.

For a split second, I feared that my mother was going to decimate this other woman verbally. Instead, when the docent called on her, my mother turned the conversation back to the art object on the wall. "Can you show us the back of the quilt?" she asked. Alas, it turned out that the docent had not been trained or equipped with white gloves for such interaction with the quilt. But I was so glad that my mother had turned the conversation back from a direction which seemed to suggest that the quilts' artistry or the quilters' intentionality might be questionable; with her question, she accorded both the respect of a fellow artist recognizing good work well done, and she implicitly instructed our tourmates about how to approach quilts as art. And she managed to do it without belittling anyone. My mother is like that; she's a teacher, after all, in all the truest senses of the word.

I have a long apprenticeship to quilting as an art, even though I have accepted that I myself will never be a quilter. My mother took up quilting when I was a baby; my first memories of her quilting are from the Christmas after my brother was born, when she was putting the yellow binding on the grandmother's flower garden quilt she made first. It wasn't an easy quilt to start with: grandmother's flower garden is a simple pattern, but it's a simple pattern made up of hexagons. Being that she made it in 1979, it's unsurprising to me that my mother chose the bright colors she did--lime, turquoise, gold, orange, red, all tied together with repetitions of bright white and bright yellow. Over the past few months, I've been giving a great deal of thought to the roots of my aesthetic values, and I have figured out (it was a duh! moment when it hit me, I'll tell you) that my mother's quilts have been perhaps my most important influence.

It's a particularly funny realization because I designed one of my master's exams to figure out why I am so enamored of novels in pieces--the great big nineteenth-century novels, heirs to the epistolary novel tradition, that show off their seams, their constructions out of letters, diaries, transcriptions, multiple narrators' testimonies, reflections on the past and tales of the present. I didn't get much of anywhere (though the question focused me in just the right way to see what I see in my research work). But I'm pretty sure that my having grown up surrounded by piles of fabric in various stages of being patterned--soft shards of cottons and tall stacks of blocks and fat folds of quilt-tops and hoops and frames of quilts-in-progress--might have had something to do with this fondness.

Now, one thing you learn when you're the attentive daughter of an active quilter is that the front of a quilt only tells half that quilt's story or presents half its artistry (if even that). To know what's happening on a quilt, to apprehend its patterns fully, to understand how its artist (or artists) pulled all its elements together, you have to look at the back of the quilt, as well. Hence my mother's question to the MFA docent. Hence our disappointment when she couldn't actually turn the corner back. And hence the MFA's decision to hang at least a few of the quilts in special frames that allowed visitors to examine them from both sides, which was some consolation.

In my house, quilts have never been just about being showy, and they have never been just about being useful. Indeed, my mother's quilts are the quintessence of useful beauty. If I take into account all the times I've slept under them, lain on couches under them, and wrapped up in them in sickness and in health, I'd have to guess that I've spent well over half the days of my life being warmed by her work, generally by more than one of her quilts at a time. (There are four on this couch right now--but that's chiefly because I brought three of them downstairs for photographs, earlier. Those three will go back upstairs with me in a little while, and then I'll have five quilts on my bed again. And these are only the full-size quilts; I haven't counted up the smaller quilted hangings and runners scattered through the house.)

Growing up literally surrounded by quilts, I learned to love the quieter signs of patient labor and creative work. I learned to love tracing geometrical shapes, finding the places where patterns seemed to turn on their heads, to become altogether other than what they'd just been, places where a square resolves into two triangles or two triangles become a diamond. The front of a pieced quilt will show off its shapes more or less kaleidoscopically, depending on the nature of its patterns. But the back of such a quilt will reflect or refract or subvert or echo or utterly undo those shapes, all according to the designs of the quilter. My mother has taken tops made up of neat geometric structures and quilted them with Baptist fans, the name for a style of quilting wherein a person stitches concentric curves as far as the arm can reach before choosing a new center and starting again. The effect is a tension of curves and corners, lines radiating in semi-circles and demarcating squares, rectangles, triangles, diamonds.

When my mother started machine-quilting about a decade ago, I was not as supportive as I might have been. Her hand-quilting is tiny and lovely, and the earliest machine-quilted pieces were rough in a way that her hand-quilted ones hadn't been for years. But like any adventuresome artist, my mother kept experimenting with her medium despite my naysaying and now produces beautiful machine-quilted work as well.