i carry your heart(i carry it in my heart)

Yes, when I was a college freshman, I was winnable with cummings poems. I felt quite deeply about them at the time; I might still, had I not been won temporarily by them all those years ago, in a relationship that was otherwise fairly disastrous, in a disaster-of-the-banal kind of way. Somehow, I don't think that my freshman boyfriend ever read or recited "i carry your heart with me," which is why somehow it seems exempt from the aura of disdain that I have to battle back from "somewhere i have never traveled" and a host of other lovely but, for me, marred poems.

With my youngest students, this morning, I had one of those classes that keeps me charged up and knowing I'm in the right line of work. The week's unexpected concatenation has left me reflecting on what it feels like to have literature move me--what it is that makes a work something to which I'll return, again and again, even when it's not on a syllabus, even when I'm not making my living by helping students understand it. The poems I've been loving my way through this week are in that class now. The poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins have been there for some time; the first time I read them and had to discuss them at a seminar table, I found myself on the brink of an outburst because I couldn't stand the clinical, purely intellectual way we were dissecting the gorgeousness of his fear and his exultation. How is it possible to read a poem like this one and then talk only of rhythm, only of how the sonnet form has been handled here?

The WindhoverIt seems obvious to me that you don't read this poem and never talk about its form; Hopkins, as a poet, was devoted to form and made the forms he had inherited do intricate, strangely beautiful things. For an example, look at the first two lines of this poem--

but no, see, that's the wrong way to start. Reread the poem first, and read it aloud. You, sitting there at your table, sitting at your desk, thinking, "But I don't like poetry," just try it. Try it, I tell you, and imagine what it is that he's asking you to see. This poet is writing, in 1877 (and revising possibly until 1879), to convey the feeling of heart-soaring he feels while watching a bird winging a breeze. His heart is in hiding but stirs for this bird. That's all you really need to know, in order to read the poem aloud, tasting it on your tongue, in your mouth, in your person. Read it aloud slowly, stumblingly if you need to, and don't worry if you don't know what the words mean. Know what they sound like, and you'll find that that's enough to get you started.

And then if you look back at the first two lines, you'll see the strangeness of Hopkins's having broken the word "kingdom" in two, having pushed "dom" ahead to the second line, so that the first line makes the bird a king, and also so that the idea of "kingdom" itself gets broken up, gets made into something different than you might have expected. This kingdom isn't one of places or dominions or buildings or earthly power. It turns out to be a kingdom of daylight--the bird is the dauphin, the prince, of this kingdom of daylight--and that kingdom is diffuse, is everywhere. (Now is the time for me to tell you that Hopkins, a Jesuit priest, dedicated this poem to Christ.) And now, if you look at the poem as a whole--skipping over a lot of other things that you should do to really savor each of those lines--you'll see that all the lines in the first stanza rhyme. Not some of them, not every other one, not pairs. All of them are -ing words. That's an innovation; sonnets generally have had very regular rhyme schemes, but not uniform rhymes. And pair a uniform rhyme with Hopkins's flights of diction, his soaring of words and dissolution of expectations for even grammar itself, and you have a sense of what Hopkins does with form.

But you don't get anywhere with this poem, I'd argue, if you stop with those kinds of points--if you don't see and say aloud that this poem's rush and tumble of syllables and sounds all adds up to his thrill, his utter ecstasy at having seen this bird, in all its beautiful majesty. You miss it all if you don't reckon with what it means for Hopkins to write, "My heart in hiding / Stirred for a bird, -- the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!" (7-8).

Now, there's much more to be said about Hopkins's "The Windhover," but I'm going to leave it for now and let you explore it on your own. (If you haven't read it aloud by now, I'll just tell you straight out that you are perversely denying yourself an aesthetic experience from which you would benefit, whoever you are. Are you embarrassed to read the poem aloud? Don't be. Be embarrassed if your embarrassment stops you. If people around you want to know why you're speaking, invite them to listen. Gift them the poem, or even just a word from the poem. I'd suggest "dapple-dawn-drawn," the perfect word when you need an adjective to describe a thing traced by the day's checkery early light. Not that I, personally, would know much about what that's like. I believe that I've made clear that I have been one acquainted with the night.)

We hit a moment about two-thirds of the way through class this morning when I realized that, unexpectedly, we were walking along in plain view of a vista of contemplation that was too good for me not to stop and point my students toward. Why is it that we don't talk more often about what it might mean to be moved by a poem, or a novel? My guess, the guess I spun for them from the head of the table, is that it's too intimate an endeavor, that it's ripe with possibilities for embarrassment or over-sharing or exposure. And so I went first, and I didn't demand that they pipe up just yet with the things that they love. I told them a short and discreet version of what has shaken me this week; I prepped them for what I hope will shake them as we take our first steps into Toni Morrison's Beloved next week; I gave them the two other titles upon which I can rely for a reading experience that never gets old, never goes stale--in fact, that grows and changes as I grow and change. (Those two titles are Middlemarch and To the Lighthouse.) After about ten minutes of my talking, I stopped and took a deep breath. Some eyes had widened around the table, but some pens had also come out and written down titles; some voices had asked for the titles of the poems I'd loved this week. "I feel as though I've just slipped open my chest and offered you my heart," I said, miming the act. We all laughed. I don't think the laugh undercut the point I'd made; after class, three or four students stopped by my end of the table to recommend books that have moved them, things that have served them as touchstones this far.

This kind of moment makes its way into nearly all of my classrooms at least once in a semester. I can't plan it; the right day for it to pay a visit generally becomes clear with only a few minutes of advance warning. But I feel it as one of the important things that happen in my classrooms: such moments of non-confessional self-revelation, of laying something vital on the line without placing inappropriate demands on my relationship with my students, are among the best ways I know to show them why I care about what we're endeavoring to do together. They are my ways of telling my students, I love that you're learning to love to learn; I want to do all I can to ensure that you're learning love itself. I can't teach them love itself, I know, but I teach in my field because literature is where I find and feel my humanity most clearly and keenly, and I teach because my heart is too big for me not to do this work, not to carry fifty or sixty hearts in my heart each semester, hoping to do my part to keep and care for them like the incubator in which we hatched chicks and ducklings (how fragile, how small, how stumbling and inquisitive) when I was in kindergarten. I can't actually sing them a love song; they wouldn't understand. But while I'm teaching them about narrative voice and temporality, about strategies and sentence structures, about rhyme schemes and rhythms, I'm also always hoping that they're learning a greater underlying lesson about the achieve of, the mastery of the thing--about the fire that can break from them then, a billion times told lovelier, and gash gold-vermillion.

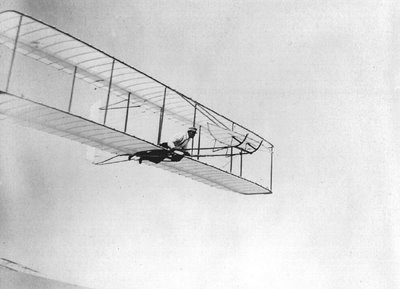

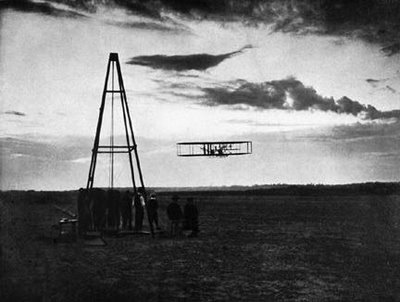

source for tonight's images: First-to-Fly's history of the Wright brothers (two of Ohio's most famous sons). The top two images are dated 1902; the last one is 1908.

1 Comments:

1] Thank you for reminding me of why I love to teach, especially right before the campus visit.

2] Thank you for reminding me why I love art -- sometimes I forget. Your last couple of post have had me thinking about art that I love and got me thinking about Felix Gonzalez-Torres again. If you haven't run inot "Untitled" [Death by Gun] yet, you should.

Post a Comment

<< Home