Postcard days.

Today was a postcard day in lovely Gambier--still is, in fact, since the sun (glorious sun! glorious daylight saving time!) hasn't yet gone down, which means that even out the east-facing front of my house, the light is good and interesting, while out the west-facing back of the house, I can see the sun still glittering behind the woods, throwing the thin tall trees into black relief. And it is nearly 7:30. Tomorrow, says my weather site, will be 2 minutes and 38 seconds longer. And this time tomorrow, barring disaster (the art of losing isn't hard to master), I'll be buckled into a plane, taxiing down a runway, on the first leg of a late-evening trip to a late-week conference in Canada.

Today was a postcard day in lovely Gambier--still is, in fact, since the sun (glorious sun! glorious daylight saving time!) hasn't yet gone down, which means that even out the east-facing front of my house, the light is good and interesting, while out the west-facing back of the house, I can see the sun still glittering behind the woods, throwing the thin tall trees into black relief. And it is nearly 7:30. Tomorrow, says my weather site, will be 2 minutes and 38 seconds longer. And this time tomorrow, barring disaster (the art of losing isn't hard to master), I'll be buckled into a plane, taxiing down a runway, on the first leg of a late-evening trip to a late-week conference in Canada.  I'm thinking a lot about postcards and traveling today, not least because I have miles to go before I sleep, and not least because in my afternoon class today, we discussed Mary Kingsley's unexpectedly delightful Travels in West Africa (1897), the narrative of Kinglsey's arduous, adventurous, sometimes utterly foolish, sometimes bottomlessly problematic, always splendidly enthralling expedition by foot and canoe through western Africa (Gabon, to be specific, then called the Congo Français) in 1895, when she was 33. She had been to Africa once already, in 1892, shortly after her parents died and she suddenly found herself relatively free from responsibility. (Not entirely free, because she still had a brother to worry about. But relatively free.) She decided to expend her energy on learning the tropics. Because she could not afford to go all the way to Malaysia, she went to Africa. She was looking for fish and fetish. She was looking to describe what she found on this (to her) unfamiliar continent, not what she thought it should be or what its deficiencies were, in comparison with her dreams. She eschewed most stereotypically European or English ways of behaving on the continent--did not ask to be carried around; taught herself to paddle a canoe over rapids; dutifully and even a little gleefully took her turn finding fords through swamps, when one person had to venture in ahead of the others so that they all wouldn't end up in over their heads. But the unanimous winner of our collective favorite moment of the day's reading occurs when Kingsley sings the praises of one trapping of European propriety she didn't eschew: her skirt. Because Kingsley moved more slowly than the Fang people with whom she was traveling (as the only European and the only woman), while they rested, she would walk on ahead, and then they would catch up with her. At one point, this routine became thorny indeed:

I'm thinking a lot about postcards and traveling today, not least because I have miles to go before I sleep, and not least because in my afternoon class today, we discussed Mary Kingsley's unexpectedly delightful Travels in West Africa (1897), the narrative of Kinglsey's arduous, adventurous, sometimes utterly foolish, sometimes bottomlessly problematic, always splendidly enthralling expedition by foot and canoe through western Africa (Gabon, to be specific, then called the Congo Français) in 1895, when she was 33. She had been to Africa once already, in 1892, shortly after her parents died and she suddenly found herself relatively free from responsibility. (Not entirely free, because she still had a brother to worry about. But relatively free.) She decided to expend her energy on learning the tropics. Because she could not afford to go all the way to Malaysia, she went to Africa. She was looking for fish and fetish. She was looking to describe what she found on this (to her) unfamiliar continent, not what she thought it should be or what its deficiencies were, in comparison with her dreams. She eschewed most stereotypically European or English ways of behaving on the continent--did not ask to be carried around; taught herself to paddle a canoe over rapids; dutifully and even a little gleefully took her turn finding fords through swamps, when one person had to venture in ahead of the others so that they all wouldn't end up in over their heads. But the unanimous winner of our collective favorite moment of the day's reading occurs when Kingsley sings the praises of one trapping of European propriety she didn't eschew: her skirt. Because Kingsley moved more slowly than the Fang people with whom she was traveling (as the only European and the only woman), while they rested, she would walk on ahead, and then they would catch up with her. At one point, this routine became thorny indeed:

Now, I love having class meetings where some large proportion of the people at my table exclaim, "I loved that." And this passage brought down the house.About five o’clock I was off ahead and noticed a path which I had been told I should meet with, and, when met with, I must follow. The path was slightly indistinct, but by keeping my eye on it I could see it. Presently I came to a place where it went out, but appeared again on the other side of a clump of underbush fairly distinctly. I made a short cut for it and the next news was I was in a heap, on a lot of spikes, some fifteen feet or so below ground level, at the bottom of a bag-shaped game pit.

It is at these times you realise the blessing of a good thick skirt. Had I paid heed to the advice of many people in England, who ought to have known better, and did not do it themselves, and adopted masculine garments, I should have been spiked to the bone, and done for. Whereas, save for a good many bruises, here I was with the fulness of my skirt tucked under me, sitting on nine ebony spikes some twelve inches long, in comparative comfort, howling lustily to be hauled out.

I realize that I still haven't told you what I mean by calling today a postcard day.

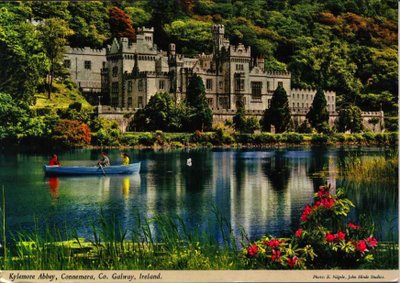

You will recall that yesterday began (for me, late riser) with a sunny flourish; I missed the first round of rain and awoke to a clear gleaming wetness and clouds that kept flying. But you will also recall that yesterday ended in wind and cold (and, by the time it was all over but the shouting, moon and starshine--so, no wholehearted complaints). Today, we had gusty wind again, all day long, and the temperature didn't climb all that high, but the aesthetics of the day were just splendid: rich, hueful, saturated blue, clear and constantly changefully beauteous. The grass is greening extravagantly from all this rain and all this sun, and the overall result is not unlike a John Hinde postcard, such as the one at the top of this writing.

I fell in love with John Hinde postcards during the year I lived in England, a decade ago. I chased them throughout the United Kingdom, always looking out for their brilliantly artificial and luridly lovely colors, their improbably prosaic foreground details (often at monumental places), their occasional descent into utter bourgeois banality. Somehow, despite my looking for them constantly, I came home at the end of the year with only a few. I've picked up a few more on research trips over the years, and once I even received one in the mail from Ireland. That one, in fact, is perhaps my favorite--enough so that I'm scanning it in for you.

I mean, come on. You have to love that--who puts a rowboat full of people right in the middle of a souvenir image of an Irish abbey? And then endows it (and especially them) with some of the brightest colors in the image? John Hinde Studios, that's who. And if you want to know much more about John Hinde than I'm prepared to tell you here and now, visit the British website "I Like" and check out the page dedicated to his work. Be sure to search out the Butlins images, which are simply fantastic.

You know who else loved picture postcards, or who was at least drawn to working with them? Roland Penrose, the surrealist artist. He did a number of works that used multiples of the same card to create strange and wonderful effects. The image on the main page of the Roland Penrose website is currently one of those postcard collages.

I'm not so good at sending postcards, myself. I've wondered about this many times. I can remember being good at writing postcards; the summer I studied in Greece, I sent postcards to everyone I knew, sometimes more than once. I remember, in particular, sitting with friends at a café near the water in Xania, on Crete, and writing postcards. We were all writing postcards. I was working on a postcard to my grandfather, and I was trying to write in handwriting larger than my usual tight and tiny postcard scrawl, trying to make sure that he would be able to read it when it arrived, and that he would enjoy it. My grandmother had died nearly a year earlier. I was certain (and I'm certain I was correct) that my grandfather was terribly lonely, alone in his house, in a city rapidly become inhospitable.

When I was about to leave for my year in England, a few months later, he sat me down with the National Geographic Atlas of the World--the same atlas I inherited at his death, the same atlas that now holds my advanced degree diplomas--and, after I'd shown him where I'd be living and studying, demanded that I stay away from Northern Ireland, no matter what. By the time I'd been in England for two months, he was the one who had had his life nearly ended, in a terrible car accident in Detroit. Because I was in England, preoccupied with all that it meant for me to be living in England, I didn't grasp the magnitude of what was happening until I flew home for a surprise visit at Christmas. My grandfather was still in the hospital, his head in a halo and his body in traction, his mind leaving us for a place from which he'd only send back the briefest, most poignant of dispatches, at moments when we least expected them. The first time I saw him after the accident, he called me my old childhood nickname, the one he called me when we hadn't yet attacked my always-unruly hair with the white rattail comb and clear-handled hairbrush my grandmother kept in the downstairs bathroom. "Subtlekopf," he called me, for the first time in fifteen years. We still don't know how that nickname translates, literally. I know that "kopf" is "head" in German (which he'd grown up speaking, up on the farm in Bad Axe), so I imagine that "subtle" has some meaning that leaves the whole nickname signifying "Messy head." In the absence of any more solid definition--in the absence, that is, of an answer likely never to come, just as I'm likely never to get back the Polish lullaby my great-grandmother sang to me, only a couple of years before I'd read to her from the Louis Pasteur book, our favorite among the batch of books my grandmother kept on hand for her grandchild, voracious for words above most other things--I prefer to think of it as his early prognostication of what I'd come to value, what I'd aspire to embody, as I grew.

Funny how this writing wanders, how the unanticipated signpost appears to signal a scenic route, how I'm always willing to follow, knowing I'll be hushed and humbled by what is found there.

Near the end of his life, my grandfather sent back one of his most wrenching postcards from Alzheimer's. One evening, my mother had just arrived at his nursing home, where she fed him dinner every night and lunch every weekend day from the time she and my father moved him to Indiana a year after his accident. "How was your day, Papa?" she asked him.

"How should I know?" he replied. "I wasn't here."

sources for tonight's images: 1) The Airliner Showroom Sale of Airline and Airport Postcards (I didn't go searching through these; I'll be there are some in this batch that would rival the stuff in Boring Postcards...); 2) a brief biography of Mary Kingsley.

7 Comments:

At the risk of exploding a fond memory...

Was it Salatkopf, by any chance? (This translates as "salad head").

Sorry -- scratch that. "Salatkopf" translates as "head of lettuce."

German speakers in the house: could it be "sattelkopf"? And if so, what would "saddlehead" mean as a nickname? I am almost too sad even to ask, because a word with no definite meaning can mean everything I need it to.

I must say I love the idea of your grandfather calling you "lettucehead" -- a nickname which would be consistent with (for instance) "mon petit chou" -- "my little cabbage" -- in French. But perhaps you are right -- that it is better not to know.

None of my grandparents had a cool nickname for me, though my paternal grandfather insisted on calling me by the name of "Nabeel"; that was the name that he wanted me to have (and the one I would have had -- had my mother not insisted on something less dreadful). He persisted in calling me Nabeel for over a decade, but thankfully had lost interest in this bit of onomastic resistance by the early 1990s.

I think I can be of assistance here: The word is "zottelkopf", which means "shaggy head". It's from a children's story about the Olchis, who are nice monsters who love stinky things...

"Sie schüttelt heftig ihren Zottelkopf, und die steifen Olchi-Haare scheppern wie Metall. Olchis schneiden ihre Haare nie."

Oh! Thank you, whoever you are! That would all make a lot of sense, because I was definitely (am still definitely) very much a shaggy head.

Bravo to anonymous for solving the mystery!! (However, I reserve the right to call Dr. S "Salatkopf" from now on).

Post a Comment

<< Home