Orion, be my guide.

When I was in college, I had two dorm rooms: one was my actual, school-assigned room (my senior year, on the third of the east-facing side of a historic dorm, so that I had beautiful views of the sun rising every morning while I finished writing my senior thesis), and the other was the third floor of the building next door, the beautifully and aptly named Ascension Hall. The third floor of Ascension Hall is a reading room, replete with stained glass and hardwood floors and high, beamed ceilings. I moved in every evening after dinner and stayed at my heavy wooden table, beside the heater and the window, until security came to lock up the building and kick me out at 2 a.m. Some evenings I got lucky, and they didn't show up until 2:30. I was always the tiniest bit resentful that I was being made to go home; now I realize that had they not booted me out of the reading room every night, I would probably never have slept in my own bed. As it was, by the time I got home, the fraternity guys who lived below me were usually asleep, or at least quiet, and so I could either keep working or (as more usually happened) fall into bed for a few hours before getting up and starting the whole routine over again.

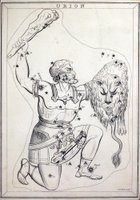

When I was in college, I had two dorm rooms: one was my actual, school-assigned room (my senior year, on the third of the east-facing side of a historic dorm, so that I had beautiful views of the sun rising every morning while I finished writing my senior thesis), and the other was the third floor of the building next door, the beautifully and aptly named Ascension Hall. The third floor of Ascension Hall is a reading room, replete with stained glass and hardwood floors and high, beamed ceilings. I moved in every evening after dinner and stayed at my heavy wooden table, beside the heater and the window, until security came to lock up the building and kick me out at 2 a.m. Some evenings I got lucky, and they didn't show up until 2:30. I was always the tiniest bit resentful that I was being made to go home; now I realize that had they not booted me out of the reading room every night, I would probably never have slept in my own bed. As it was, by the time I got home, the fraternity guys who lived below me were usually asleep, or at least quiet, and so I could either keep working or (as more usually happened) fall into bed for a few hours before getting up and starting the whole routine over again. One of my favorite parts of the whole process of packing up and walking home was that for most of the winter, during the three minutes I was outside, walking from building to building, I could see the constellation Orion somewhere in the sky. Some nights, I think I actually talked to him. I have clear visual memories of the ink-blue vast of sky between Ascension and my dorm, over the trees that dot the slope eastward away from campus, and those tell-tale nine bright stars suspended there to my side. It wasn't long, my sophomore year, before I thought of Orion as my escort home, the figure that would be waiting when I pushed open the heavy wooden south door of Ascension, walked down the stone steps, and paced along the walkway to the room where my roommate lay sleeping already. (She left the light burning low for me, though. I always thought that was nice of her. That year, we lived in the basement, and our windows were like portholes, resting at ground level. You may remember this detail from my explanation of why I don't like reggae. Anyhow, the windows always glowed quietly, making it all the easier to bid Orion goodnight and go inside and down some more stairs. Going back to that subterranean room, after the loftiness of Ascension's top floor, felt like true descent.) When I found Robert Frost's line "I have been one acquainted with the night" during my senior year, I felt as though I'd finally located myself in verse.

One of my favorite parts of the whole process of packing up and walking home was that for most of the winter, during the three minutes I was outside, walking from building to building, I could see the constellation Orion somewhere in the sky. Some nights, I think I actually talked to him. I have clear visual memories of the ink-blue vast of sky between Ascension and my dorm, over the trees that dot the slope eastward away from campus, and those tell-tale nine bright stars suspended there to my side. It wasn't long, my sophomore year, before I thought of Orion as my escort home, the figure that would be waiting when I pushed open the heavy wooden south door of Ascension, walked down the stone steps, and paced along the walkway to the room where my roommate lay sleeping already. (She left the light burning low for me, though. I always thought that was nice of her. That year, we lived in the basement, and our windows were like portholes, resting at ground level. You may remember this detail from my explanation of why I don't like reggae. Anyhow, the windows always glowed quietly, making it all the easier to bid Orion goodnight and go inside and down some more stairs. Going back to that subterranean room, after the loftiness of Ascension's top floor, felt like true descent.) When I found Robert Frost's line "I have been one acquainted with the night" during my senior year, I felt as though I'd finally located myself in verse.What has always made seeing Orion all the more exceptional, to my mind, is that I generally can't see constellations. I, like nearly everyone else (I suspect), can pick out the Big Dipper. Sometimes I think I can see Cassiopeia's big W. But Orion is the only non-Dipper I'm truly confident I'm seeing, and every fall I wait for his reappearance on my eastern horizon. In Ithaca, one year, I saw him first in the southwest, as he prepared to sink below the horizon at dawn, when I had just shown up to wait in line for the opening of the Friends of the Library book sale. I was so excited that I pointed it out to the people with whom I was standing. One of these people, who was breaking my heart slowly but surely, then had to point the constellation out to the woman who, I found out later, was his girlfriend; she didn't recognize it, may not have known it at all. I held this fact against her. The silliness of that whole situation defied reason.

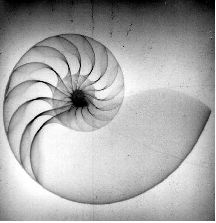

My inability to see constellations--which also, to my mind, defies reason--partners up with a couple of similar, and similarly galling, incapacities. Some power must be on my side this morning, because of the two that just popped to mind, the only one that's stayed around long enough to make it into words is that when I have gone shelling, I have had an excruciatingly hard time being able to see good shells. I want to have an eye for all things detailed, all things rare and collectible and deserving of vision, and when I can't see them, I feel inordinately frustrated with myself. I don't need to have anyone draw me an umbrella in the sky at a party. I'd like to be able to see the pictures others have seen up there in the firmament. I want to find the rare chambered nautilus, the lovely sand dollar, the once-in-a-lifetime seahorse. I don't want to forget the beautiful word. (Perhaps my encouraging students to recirculate dying or forgotten words has come from this longing; I don't want them to miss these things, either.) I feel slightly less alone in my frustration with constellation-seeing now that I know Thomas Carlyle felt it too; apparently he once asked, "Why did not somebody teach me the constellations, and make me at home in the starry heavens, which are always overhead, and which I don't know to this day?"

My inability to see constellations--which also, to my mind, defies reason--partners up with a couple of similar, and similarly galling, incapacities. Some power must be on my side this morning, because of the two that just popped to mind, the only one that's stayed around long enough to make it into words is that when I have gone shelling, I have had an excruciatingly hard time being able to see good shells. I want to have an eye for all things detailed, all things rare and collectible and deserving of vision, and when I can't see them, I feel inordinately frustrated with myself. I don't need to have anyone draw me an umbrella in the sky at a party. I'd like to be able to see the pictures others have seen up there in the firmament. I want to find the rare chambered nautilus, the lovely sand dollar, the once-in-a-lifetime seahorse. I don't want to forget the beautiful word. (Perhaps my encouraging students to recirculate dying or forgotten words has come from this longing; I don't want them to miss these things, either.) I feel slightly less alone in my frustration with constellation-seeing now that I know Thomas Carlyle felt it too; apparently he once asked, "Why did not somebody teach me the constellations, and make me at home in the starry heavens, which are always overhead, and which I don't know to this day?"I thought a lot about Orion as I drove home last night, in part because I'm thinking I may be doing this late-night drive home through mid-Ohio more often, and in part because I realized that I haven't seen him yet this winter, even on my late-night walks home. When I walk home now, I'm northward bound; Orion seems elsewhere. More often, I'm driving home, skittish as ever about a half-mile walk along a dark street, even in my tiny village. The night before our last day of classes last fall, I broke my own record and headed home from the office at 3:30 a.m. It was about 15 degrees outside; I had wrapped my scarf around my head, babushka style, because I hadn't bothered to take a hat with me when I went to work in the afternoon. The whole world was silent, asleep.

The highway felt like that last night; I killed my brights as I slipped through Centerburg and Mt. Liberty and Bangs, figuring that even if the people in those houses nestled up against the road are used to mid-night street-roar and light-flash, I could do my part to help them keep sleeping--particularly because, I'm coming to realize, I may take my abilities to sleep like a rock a bit too much for granted. In Centerburg, all the stoplights had been turned to flashing yellows; people still had their Christmas lights up, and I saw the dog-sized wire-and-lights fake deer that I find so funny (because last year, when my parents picked up a pair for our yard in Indiana, our dog was utterly perplexed by this inanimate thing her own size but with none of the smells she expects from fellow animals). One house also had one of those outdoor projectors, a latter-day magic lantern, projecting "Let it Snow" onto its side. I kept waiting for everything to add up, but instead I think I'm supposed to be suspended in a happy, slightly discombobulated anticipation for a little while longer, getting acquainted with the night in a new way, relearning my landscapes yet again.

The highway felt like that last night; I killed my brights as I slipped through Centerburg and Mt. Liberty and Bangs, figuring that even if the people in those houses nestled up against the road are used to mid-night street-roar and light-flash, I could do my part to help them keep sleeping--particularly because, I'm coming to realize, I may take my abilities to sleep like a rock a bit too much for granted. In Centerburg, all the stoplights had been turned to flashing yellows; people still had their Christmas lights up, and I saw the dog-sized wire-and-lights fake deer that I find so funny (because last year, when my parents picked up a pair for our yard in Indiana, our dog was utterly perplexed by this inanimate thing her own size but with none of the smells she expects from fellow animals). One house also had one of those outdoor projectors, a latter-day magic lantern, projecting "Let it Snow" onto its side. I kept waiting for everything to add up, but instead I think I'm supposed to be suspended in a happy, slightly discombobulated anticipation for a little while longer, getting acquainted with the night in a new way, relearning my landscapes yet again.Today's postscript: I read myself to sleep last night with more Standage and, aptly enough, came across this very sweet anecdote from Thomas Edison's diary:

Even in my courtship my deafness was a help. In the first place it excused me for getting quite a little nearer to [his second wife, Mina] than I would have dared to if I hadn't had to be quite close in order to hear what she said. My later courtship was carried on by telegraph. I taught the lady of my heart the Morse code, and when she could both send and receive we got along much better than we could have with spoken words by tapping out our remarks to one another on our hands. Presently I asked her thus, in Morse code, if she would marry me. The word "Yes" is an easy one to send by telegraphic signals, and she sent it. If she had been obliged to speak it, she might have found it harder. (qtd. in Standage 142)I feel as though David Brooks, who wrote an amusingly befuddled "what are the kids up to these days?" column about online communities for Sunday's Times, ought to read Standage's chapter on love over the telegraph wires and the kinds of online communities that sprang up when telegraph operators suddenly found themselves all connected on the job. People played chess and checkers, told dirty jokes, hooked up with fellow operators, helped other non-operators hook up (and even get married) online--lots of the kinds of things that happen in these systems that Brooks thinks might be a sign that we "kids" might not be growing up, or some such thing. Amusingly, within the last month, I've also watched as a blogger on another site I frequent has blown onto the scene and started chiding longer-standing bloggers about the fact that they're blogging rather than getting out into the world and meeting people; it's a little appalling, really, and provoked my ire one time when she got snippy with someone whose stuff I've really enjoyed reading. Mainly, what all this is adding up to is that, as usual, things are more complicated than they at first appear--and none of us may be doing any new things at all. I don't love the Barenaked Ladies, but I think that one song (despite its annoying "woo hoo hoo!" hoots) espoused a philosophy of history that might not be all wrong.

sources for today's images: 1) Hubblesite; 2) University of Oklahoma's History of Science online exhibitions; 3) MIT's Nuclear Reactor Laboratory (image by W. Fecych); 4) an online 1895 atlas.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home