Making connections

This afternoon my brain is multi-tasking, whether or not I want it to: I'm building syllabi, trying to trace out the throughlines that will make all this material comprehensible to the kiddoes who are preparing to return to this little academic village, and today that means I'm reading about the development of telegraphy. You may already be able to sense the way connections will start to proliferate. It's a bit mind-boggling, really (and I don't need a Freudian genius to tell me why I just slipped and typed "mind-blogging"): once telegraphy really got going--which took awhile, even once the technology had been worked out (which took its own while), since people at first thought of it as a spectacle, rather than an everyday-useful phenomenon--networks sprouted like strange plants, across oceans, between countries, between cities, within cities, within buildings. I'm loving the hopes that people had for the telegraph; by 1880, Tom Standage tells us in The Victorian Internet, 100,000 miles of undersea cable were connecting the world, and people were prognosticating peace as a result:

This afternoon my brain is multi-tasking, whether or not I want it to: I'm building syllabi, trying to trace out the throughlines that will make all this material comprehensible to the kiddoes who are preparing to return to this little academic village, and today that means I'm reading about the development of telegraphy. You may already be able to sense the way connections will start to proliferate. It's a bit mind-boggling, really (and I don't need a Freudian genius to tell me why I just slipped and typed "mind-blogging"): once telegraphy really got going--which took awhile, even once the technology had been worked out (which took its own while), since people at first thought of it as a spectacle, rather than an everyday-useful phenomenon--networks sprouted like strange plants, across oceans, between countries, between cities, within cities, within buildings. I'm loving the hopes that people had for the telegraph; by 1880, Tom Standage tells us in The Victorian Internet, 100,000 miles of undersea cable were connecting the world, and people were prognosticating peace as a result:An ocean cable is not an iron chain [wrote Henry Field, the brother and biographer of Cyrus Field, one of the great financiers of telegraphy on the American side of things], lying cold and dead in the icy depths of the Atlantic. It is a living, fleshy bond between severed portions of the human family, along which pulses of love and tenderness will run backward and forward forever. By such strong ties does it tend to bind the human race in unity, peace and concord.... it seems as if this sea-nymph, rising out of the waves, was born to be the herald of peace. (qtd. in Standage 104)But my favorite detail, so far, is the pneumatic tube system designed in the 1860s to relieve blockages at major exchange points:

Consider, for example, the path of a message from Clerkenwell in London to Birmingham. After being handed in at the Clerkenwell Office, the telegraph form would be forwarded to the Central Telegraph Office by pneumatic tube, where it would arrive on the "Metropolitan" floor handling messages to and from addresses within London. On the sorting table it would be identified as a message requiring retransmission to another city and would be passed by internal pneumatic tube to the "Provincial" floor for transmission to Birmingham by intercity telegraph. Once it had been received and retranscribed in Birmingham, the message would be sent by pneumatic tube to the telegraph office nearest the recipient and then delivered by messenger. (Standage 99)The mental image this passage offers me nicely figures not just the way syllabi in general come together but also the strange and intriguing ways my classes always seem to map onto one another: telegraph networks link up to neural networks link up to networks of writers, publishers, and readers link up to intratextual networks of characters and plot events link up to intertextuality itself, and on and on. As a bonus gift, I also get to wish that there were a commuter rail network--not even anything as racy as pneumatic tubes, just plain old trains--in central Ohio, so that I could be transported down to Columbus for my dinner and movie tonight without having to drive myself there and back--because, well, driving is too slow, and too attention-consuming, when what I want to be able to do is sit and look out the window at the winter fields (the occasional one turning green with winter wheat) and daydream about what I'm on my way to. Because my brain assuredly won't stop multitasking when I hop in the car later, I'm sure I'll still be daydreaming, but its lion's share will be checking the rear-view mirror, not the herds of moseying cows at the side of the road, and on the way home the deer-checking will certainly require everything I've got.

Oh. Oh no.

As my craazy goddess friend would say, Oh. Holy. Jesus. I just googled "herd of cows" to make sure I was using the correct group-name (I have been laughed at in the past, I am sure, for misusing words like "flock"), and Hit #5 was a blog where the following post landed this guy on my list. And so, today's postscript (or post-script?):

MY IPOD IS A GLORIFIED HERD OF COWSGood Lord. I have never once thought of my iPod as a second dick. I feel fairly confident in saying that I wouldn't think of it as a second dick even if I had a first dick. I'll let you count the number of things sheerly wrong with that post, but I suspect that my favorite is the blithe assertion "in fact I am so rich that I could afford three iPods." Yeah, big spender!

I bought an iPod recently, but I never listen to it. Music is a substitute for action: deeds are my music. The only reason I have it is that otherwise people would think I couldn’t afford one, when in fact I am so rich I could afford three iPods. It just hangs from my belt like a second dick, a badge of status like cattle to an African tribe. Me big chief.

Since I bought it last month I have had more than 800 women.

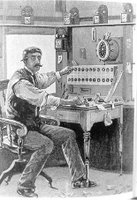

source for today's image: A National Park Service oral history of telegraphy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home