A door. A gate. A door.

I've been a sometimes reluctant believer in signs for quite some time now. When I was trying to decide on a graduate school, I had two equally attractive options. My heart and self-interest tugged me from one to the other to the one to the other until I was exhausted and overwhelmed, worried that I would make the wrong choice and deform my life forever afterward. Finally, in a moment of utter resignation, I asked my mother what she thought I should do. "Pray for a sign," she replied. I told her that I didn't think praying for a sign was a good idea this time. "Just do it," she said. So I did. And just so you know, when you roll your eyes while you pray for a sign, this kind of stuff happens: you go to your campus bookstore thirty minutes later to make some photocopies, and while you're paying for those copies, you look down, and you discover that (bearing in mind that Cornell was one of the two options) the bookstore has twenty copies of Anita Desai's Journey to Ithaca in the showcase under the cash register. You didn't even know there was a showcase under the cash register. In three years on campus, you've never seen this case. And now, thirty minutes after you asked for a way to decide between Cornell and another school, you've been told--twenty times, no less--to journey to Ithaca.

I've been a sometimes reluctant believer in signs for quite some time now. When I was trying to decide on a graduate school, I had two equally attractive options. My heart and self-interest tugged me from one to the other to the one to the other until I was exhausted and overwhelmed, worried that I would make the wrong choice and deform my life forever afterward. Finally, in a moment of utter resignation, I asked my mother what she thought I should do. "Pray for a sign," she replied. I told her that I didn't think praying for a sign was a good idea this time. "Just do it," she said. So I did. And just so you know, when you roll your eyes while you pray for a sign, this kind of stuff happens: you go to your campus bookstore thirty minutes later to make some photocopies, and while you're paying for those copies, you look down, and you discover that (bearing in mind that Cornell was one of the two options) the bookstore has twenty copies of Anita Desai's Journey to Ithaca in the showcase under the cash register. You didn't even know there was a showcase under the cash register. In three years on campus, you've never seen this case. And now, thirty minutes after you asked for a way to decide between Cornell and another school, you've been told--twenty times, no less--to journey to Ithaca.I journeyed to Ithaca.

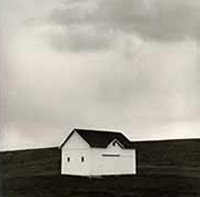

My peregrinations tonight landed me in front of the Kenyon Authors section, where I had hoped to find a couple of James Wood books, since I'm gathering together essayists. Alas, no James Wood, though he was a Kenyon faculty member for a semester several years ago, and usually that's enough to garner one a space on the Kenyon Authors shelf. While I was crouched near the ground looking at the Ws, though, I rediscovered copies of Grace and On Nantucket, the two books of photographs that my provost, Greg Spaid, has published. I want to show you pictures from Spaid's book, but they're only available in good reprints on a gallery's webpage, and I really, really don't want to pull any of them off the site (even for you, even with credit), since they're directly connected with my chief academic officer. Follow the link, and you too will love them. You may even want to buy them. I know I do. (The images I am giving you, by the way, are from a web announcement of a lecture he did at a nearby university, several years ago. I'm offering them because they're tiny and you'll need to get his book(s) in order to see more clearly what all my fuss is about.)

My peregrinations tonight landed me in front of the Kenyon Authors section, where I had hoped to find a couple of James Wood books, since I'm gathering together essayists. Alas, no James Wood, though he was a Kenyon faculty member for a semester several years ago, and usually that's enough to garner one a space on the Kenyon Authors shelf. While I was crouched near the ground looking at the Ws, though, I rediscovered copies of Grace and On Nantucket, the two books of photographs that my provost, Greg Spaid, has published. I want to show you pictures from Spaid's book, but they're only available in good reprints on a gallery's webpage, and I really, really don't want to pull any of them off the site (even for you, even with credit), since they're directly connected with my chief academic officer. Follow the link, and you too will love them. You may even want to buy them. I know I do. (The images I am giving you, by the way, are from a web announcement of a lecture he did at a nearby university, several years ago. I'm offering them because they're tiny and you'll need to get his book(s) in order to see more clearly what all my fuss is about.)I decided I would try an experiment, one that's often had interesting results for me: I'd do some bibliomancy, open one of the books to a random page and interpret what I found there. If I couldn't find direction out in the bookstore, maybe I'd get some help within one of the books. Though it was Grace's title that put the idea in my head, I slipped On Nantucket off the shelf to see what would happen. I closed my eyes and dropped the book open to the portrait of a white door. A door. I closed the book. I closed my eyes. I dropped the book open to another portrait, this time of a gate, set into an ivied wall. A door, and a gate. I closed the book. I closed my eyes. I dropped the book open to a third portrait, this time of a door in a shingled wall. A door, a gate, and a door. I've paged through this book before, but not for a couple of years, and so I found myself wondering whether it's actually a book of doors and gates--of ingress and egress, comings and goings. In fact, it's not. I just happened to hit three of them in a row. Comings and goings. Ins and outs. Openings and closings. It's tough to interpret a door; it's a figure of liminality itself. Three threshold spaces in a row, on an evening when I'm looking for some kind of sign, feels like being told to sit tight and look around for just a little while more, until I can ascertain what kind of threshold I'm on, and which direction I'm going.

The last bibliomantic experience I remember clearly happened when I was studying at an English university ten years ago. This university had two libraries, conveniently (if not originally) called the Old Library and the New Library. The Old Library was a fine place to work, because its primary workspaces were divided among enormous tables in the center of the main floor and individual desks set into small bay windows popped out of the building's side (in a very industrial way, since this building was a product of the 1950s). I loved the window desks; there's little I like more than a desk at a window. I will rearrange rooms to get a desk near a window if I can. One night, I'd been working in the Old Library, taking notes for a paper on dangerous knowledge and despair in Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, and was heading out for dinner. While I waited for a friend, I stepped into the university's chapel, which was across a small courtyard from the Old Library. I was worried about this paper, worried it wouldn't be very smart, worried that I didn't have enough time to write it, worried that the ideas weren't coming together as swiftly as they did back in that mythical time that never actually happened, when the ideas came easily, thick and fast and brilliant.

The last bibliomantic experience I remember clearly happened when I was studying at an English university ten years ago. This university had two libraries, conveniently (if not originally) called the Old Library and the New Library. The Old Library was a fine place to work, because its primary workspaces were divided among enormous tables in the center of the main floor and individual desks set into small bay windows popped out of the building's side (in a very industrial way, since this building was a product of the 1950s). I loved the window desks; there's little I like more than a desk at a window. I will rearrange rooms to get a desk near a window if I can. One night, I'd been working in the Old Library, taking notes for a paper on dangerous knowledge and despair in Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, and was heading out for dinner. While I waited for a friend, I stepped into the university's chapel, which was across a small courtyard from the Old Library. I was worried about this paper, worried it wouldn't be very smart, worried that I didn't have enough time to write it, worried that the ideas weren't coming together as swiftly as they did back in that mythical time that never actually happened, when the ideas came easily, thick and fast and brilliant.And so I was looking around a little bit for a way to think through my worry--to numb it out in order to keep working, actually. I picked up a bible from the pew in front of me and thumbed it open at a random place--where my eye happened to fall first on a passage exhorting its reader not to worry, not to fret. I thought that was strange but also kind of hokey. So I closed the book. I closed my eyes. I reopened the book. And I faced this moment from Genesis: "The Lord dealt with Sarah as he had said, and the Lord did for Sarah as he had promised." Thus does the writer of Genesis mark the transition from the revelation that Abraham's aged wife Sarah will bear him a son, and from her laughingly disbelieving response to that revelation, to the fulfillment of its prophecy. This second passage gave me some pause; I put the bible back in its rack and went back outside, into the cold November night, to walk home with my friend.

One of the things I like about Greg Spaid's photographs is the intensity of their solitude; he captures that razor's edge between beautiful solitude and desolating loneness in photograph after photograph. My favorites aren't among the images I can show you tonight--except for this perfect one, of a barn in mid-Ohio--but if you enjoy these, you should seek out his work. Look for Grace's image of a gravel road stretching from the foreground into the distance, with cornfields on either side, and you'll know where I live, in more ways than one.

One of the things I like about Greg Spaid's photographs is the intensity of their solitude; he captures that razor's edge between beautiful solitude and desolating loneness in photograph after photograph. My favorites aren't among the images I can show you tonight--except for this perfect one, of a barn in mid-Ohio--but if you enjoy these, you should seek out his work. Look for Grace's image of a gravel road stretching from the foreground into the distance, with cornfields on either side, and you'll know where I live, in more ways than one.

2 Comments:

I love reading what you write. I love hearing about the inside of your head. Got nothing to contribute, just appreciation. Thanks, Disco Lady!

Thank you. And right back at you, by the way.

Post a Comment

<< Home